It is a mistake to talk about the American Civil War in a vacuum. While by definition a war that was not against a foreign power, the conflict still proved of great consequence and interest around the world, but especially on the other side of the Atlantic. The power of southern cotton to fuel the textile mills of Northern France and the English midlands meant these two nations in particular had sizable stakes in the outcome of the conflict as well as its general duration. For the Confederacy, they were in fact banking on the power of cotton. In an approach labeled subsequently as “King Cotton diplomacy,” the Confederacy used their perceived financial leverage over England and France because of their cotton crop.

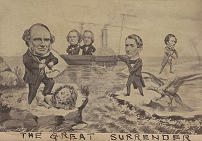

A cotton export embargo at the beginning of the war with the hopes of drawing Europe into the conflict to mediate a quick resolution ultimately did not work for the Southern cause. The Confederacy hoped for intervention, especially following the diplomatic crisis surrounding the Trent Affair. In the fall of 1861, a US naval ship stopped the British mail packet HMS Trent and removed Confederate diplomats bound for England and France. Calls rang out in Britain for war and while cooler heads ultimately prevailed, it served as an important notice to the Lincoln administration.

Cartoon about the Trent Affair

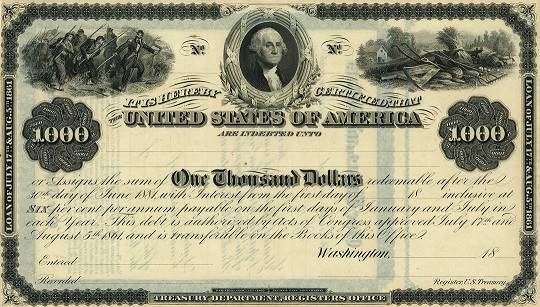

For decades prior to the war, US and British financial interests largely aligned and led many to believe that the British market might prove invaluable for the sale of Union war bonds. Yet, this did not prove to be the case. Many financiers in Britain, as well as their clients, found themselves heavily invested in the South, slavery, and cotton production. This left many in Britain quite reticent to invest heavily in American debt during the war and the market never really materialized—either for secondary sales or the larger goal of placing a loan abroad in London on the part of the US government. France similarly proved difficult. Napoleon III banned the sale of US bonds on the Parisian Stock Exchange. His hopes for a new French empire abroad likewise made Napoleon wistful for a Confederate victory to create an ally that might act as a buffer against a newly fragmented United States if the war went the way Napoleon hoped. The markets of London and Paris would not come to Washington’s aid, so it was on United States to look elsewhere.

US debt sales abroad proved most successful in the German states (namely Frankfurt) and the Netherlands (especially Amsterdam.) Frankfurt may have served as the most important market in Europe. Along the banks of the Main River, this city became the central hub for US bond sales abroad during the American Civil War. The reasons for this are many and include factors such as banking networks centered around kinship and faith that stretched across the Atlantic to places like New York City helping to facilitate these sales. But it also relied on other factors as well. For example, the US Consul officer in Frankfurt, William Walton Murphy, played a pivotal role creating a market in Frankfurt. Murphy hosted events at his residence and elsewhere where he encouraged Frankfurt bankers and everyday citizens to invest in the cause of Union and later emancipation. Such actions played a huge role in expanding US debt sales in Frankfurt and their continental network.

Note from the Amsterdam bank of Hope & Co. to banking partners in London written during the war

Amsterdam also proved important to the cause of debt sales. By the spring of 1864, US Minister to the Hague, James Pike, estimated that weekly transactions of Union bonds numbered $2 million in the city of Amsterdam alone. By the fall of that year as Americans went to the polls to reelect Abraham Lincoln, Pike claimed that US bonds consumed “an unlimited amount of capital” on the Dutch exchange. Extensive correspondence from the Dutch house of Hope & Co. and the Dutch aligned New York City firm of Fisk & Hatch both affirmed the vibrant market for US bonds in Amsterdam.

By March of 1865, banking house Knauth, Nachod & Kuhne estimated German and Dutch houses held $250 million of the $320 million in U.S. securities abroad (a low estimation in this author’s opinion.) But whatever the exact number might be is largely beside the point. For without a doubt, a very large market existed in Europe during the American Civil War for US debt, and these purchases went a long way towards stabilizing and reaffirming the legitimacy of the United States government during some of the darker days of the war.

David K. Thomson is an Associate Professor of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, USA. Thomson’s focus is on the financial history of the American Civil War era. His first book on the topic, Bonds of War, published by the University of North Carolina Press in April 2022 traces the crucially important role of bond sales by the United States government during the war to fund the conflict. Thomson’s work has also been featured in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Bloomberg. Click here for parts 1 and 2 of this blog series.

David K. Thomson is an Associate Professor of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, USA. Thomson’s focus is on the financial history of the American Civil War era. His first book on the topic, Bonds of War, published by the University of North Carolina Press in April 2022 traces the crucially important role of bond sales by the United States government during the war to fund the conflict. Thomson’s work has also been featured in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Bloomberg. Click here for parts 1 and 2 of this blog series.