Over the centuries, numerous American visitors to the Netherlands produced travel accounts, filled with their fresh insights and observations as they viewed the familiar from a foreigner’s perspective. John Romeyn Brodhead is no exception, but he was not a regular tourist. He was, or rather became, a man with a mission, hunting for history in Dutch archives.

“This is one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen,” John Romeyn Brodhead wrote in his diary on 21 October 1839. It was only his second day in the Netherlands and he had spent it well: “This morning [I] went to see the opening of the States General by the King — The day was very delightful and the whole pageant went of well —The military display was highly creditable. [..] In the afternoon [I] took a long ramble in the ‘Bosch’, a most magnificent Park in the northern end of the City.”

Parade of His Majesty the King of the Netherlands to the opening of the session of the States General (1839)

Albanians Abroad

Brodhead’s exuberance on his first trip to Europe is noteworthy. He was still a young man, the twenty-five year-old son of a prominent Dutch Reformed clergyman. He was affiliated with various Dutch-American families in upstate New York and this had facilitated his appointment as private secretary of the American chargé d’affaires, Harmanus Bleecker. The Albany lawyer and former Congressman had been appointed to the diplomatic post in The Hague by President Martin Van Buren, also of Dutch descent, who had visited the Netherlands some years previously. Finding himself in need of clerical assistance, Bleecker asked a friend, John V.L. Pruyn (another Albanian of Dutch descent), to recommend someone to take on these duties without renumeration, but with the prospect of gaining valuable experience. Brodhead’s name was put forward and a few months later he arrived in The Hague. As his responsibilities were not that onerous, Brodhead was able to indulge in reading history books and sightseeing. Gradually the young man began to contemplate his future: he determined to devote his life to history, in particular to “the contribution made by the Netherlands to the early history of the State of New York.”

There is little doubt that Harmanus Bleecker planted the seeds which came to fruition in Brodhead’s fertile mind. Bleecker and many of his friends in Albany and New York were very interested in history, particularly their own as descendants of the early Dutch colonists. In turn, Bleecker was doubtlessly aware that the government of New York State, at the insistence of the New-York Historical Society, had already made money available for exactly the purpose that Brodhead had in mind. But as yet no proper candidate for the funding had been identified. All that remained to be done was for Brodhead’s appointment to be made. In the meantime, the young man immersed himself in learning Dutch and French and experiencing everything that The Hague had to offer.

The Hague, with the “Bosch” to the right. Detail of 1852 map.

In the autumn of 1840 Brodhead’s comfortable life was suddenly disrupted. He received news that his mother’s health was declining rapidly and immediately decided to book passage on the steamer President. In October 1840, he was back with his parents in Brooklyn. Brodhead’s return to New York allowed him to contact the right people and obtain the abovementioned appointment. In January 1841 he was commissioned as agent for the State of New York. Before sailing to Europe again, Brodhead spent several weeks in Albany perusing the early records of the government of New York State, including those of Director General and Council, the colonial government of New Netherland. In this way he acquired important insights relating to potential locations for finding records in Europe. Thus equipped he began his hunt for history in England, France and the Netherlands in earnest, searching for relevant documents wherever they might be. On May 1st, Brodhead embarked on the steamship Great Western. He arrived back in The Hague on May 23rd, 1841 and did not waste time in getting started on his mission.

Request to grant Brodhead access to the National Archives of the Netherlands

The next day, Bleecker’s status as diplomatic envoy facilitated Brodhead’s introduction to the Dutch Minister for Foreign Affairs. Within a few days, an audience was arranged with the King of the Netherlands, Willem II, who had acceded to the throne just a few months earlier. “His manner was very kind and courteous,” Brodhead noted in his diary: “He spoke to me about my mission — about my having been here before — said I looked somewhat older now — [He] expressed his interest in the object I had in mind and then made many enquiries about the U.S. [and about] steamships particularly.” The King also said he hoped to see Brodhead at the palace again. Brodhead was pleased with his reception by the King: “I must say I was much more gratified at my audience than I had anticipated I would be.” Contact with the Minister of the Interior, in charge of the archives, immediately ensued, and on June 3rd, 1841, J.C. de Jonge, Chief Archivist of the National Archives of the Netherlands, was ordered to provide all possible assistance. Everything was now in place for Brodhead to start his work properly.

On June 6th, John Romeyn Brodhead opened a package of newly arrived American newspapers. Almost immediately, his eyes fell upon a death notice in the Albany daily: “At Brooklyn, yesterday morning, Eliza, wife of the Rev. Dr. Brodhead, and daughter of the late John N. Bleecker, of this city.” John’s mother had died just five days after he had embarked for Europe. Upon receiving the news he wrote an emotional entry in his diary: “O! My God! What dreadful news I just read—My dear Mother is dead! Just one month ago she left this world of pain and suffering for a bright and glorous as I fully believe—I can scarcely believe it—but it must be so.”

Discovering Documents

Over the next few months, Brodhead’s thoughts must surely have turned to his mother as he trawled through bundle after bundle of seventeenth-century documents, looking for material that suited his purpose. In a sense, he was little different from modern-day historians, who spend their time eagerly copying—previously by xerox, these days digitally—every document of potential interest. Brodhead did not do his own copying, however. Instead he enlisted the services of chartermeester J.A. de Zwaan, member of staff at the National Archives of the Netherlands. De Zwaan pencilled remarks on many documents in the collections, marking them “Copied for New York.” In gratitude for his services, De Zwaan later received a letter of thanks from the Governor of New York, while the New-York Historical Society appointed him as a corresponding member.

Title page of the manuscript version of the Remonstrance of New Netherland,(1649)

Brodhead was quite pleased with the material that he had sourced in The Hague. The records of the States General yielded much information on New Netherland and New Amsterdam. He surmised, however, that further riches awaited him in Amsterdam for he presumed that the archives of the West India Company would be the real treasure trove. In late August Brodhead therefore travelled to Amsterdam and went to see Mr. De Munninck, who was in charge of the papers. As Brodhead wrote in his diary that evening, De Munninck “at once dashed all my hopes by saying that all the old papers of the Co. previously to 1700 had been burnt up” some twenty years earlier. De Munninck promised “to make a further search to see if any thing has escaped the general vandalism.”Brodhead was greatly dispirited, but hoped that some remnants might still come to light. He also put notices in Dutch newspapers asking the public to notify him if they had anything of relevance in their possession.

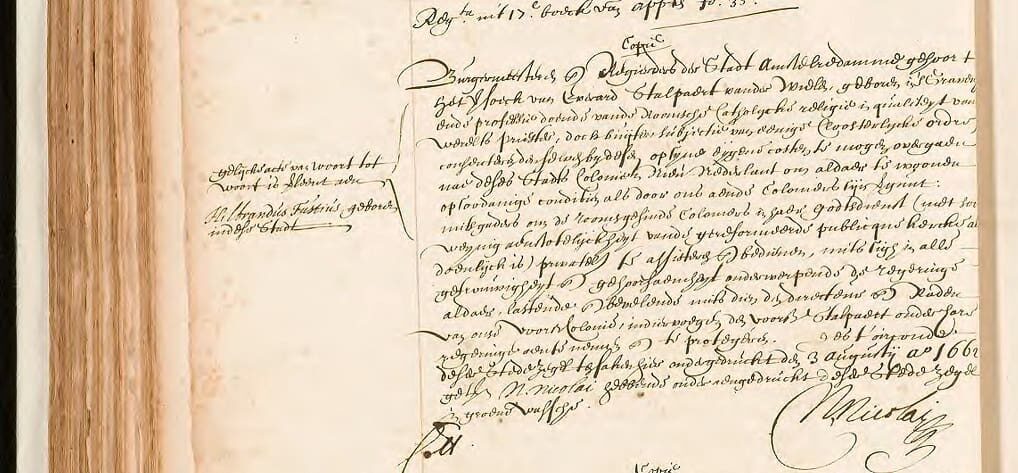

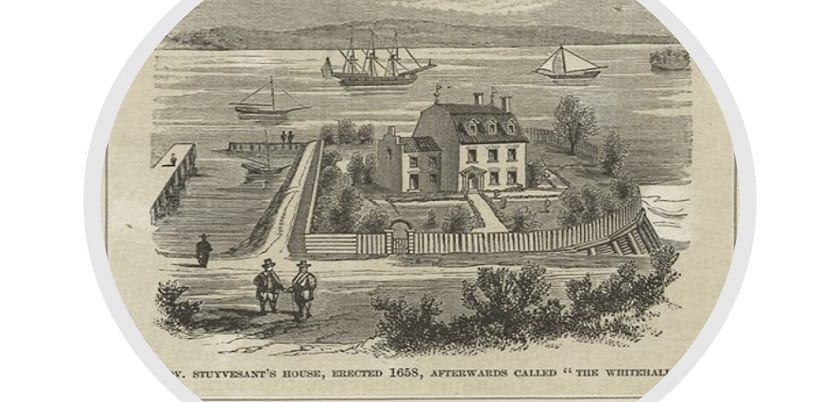

Fortunately, Brodhead at least had other options in Amsterdam. His weeks of perusing the records in Albany had taught him that the city of Amsterdam had played a vital role in New Netherland, especially through its involvement in the city-colony of New Amstel on the Delaware. Brodhead therefore established contact with city officials and had no trouble in gaining access to the Stadhuis. He found much of historical value there, but did not locate all the relevant documents. For instance, Brodhead included the contract of the city of Amsterdam with Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy and a number of Mennonite families to sail to New Amstel. Yet he omitted the travel permit granted by Amsterdam to two Catholic priests, Everard Stalpaert van der Wiele and Hilbrandus Fustius. They were even permitted to assist and serve the Catholic colonists, albeit “privately” and with “as little offence to the reformed public church as is possible.” This document is contained in the same volume as the Plockhoy contract, just five pages ahead of it. Did Brodhead simply miss this? Or did it challenge his vision of the United States as a bulwark of Protestantism in which there was no place for Catholics?

Brodhead’s other stop in Amsterdam was the Dutch Reformed Church. Its counterpart in the United States, the Dutch Reformed Church in America, had been under the supervision of the classis of Amsterdam until the late eighteenth century and only dropped the word Dutch from its name a few decades after Brodhead’s original research. Gaining access to the archives of the Amsterdam classis was even easier in this case as it did not require government permission. Brodhead was allowed to copy relevant passages from the proceedings of the classis and anticipated what he called in his diary “a present of many valuable original papers from America — Deo favente.” The “present” consisted mostly of seventeenth and eighteenth-century letters written by the New Amsterdam and New York ministers to the classis in Amsterdam. Brodhead initially mentioned in his correspondence that he received these on loan for four years, to be copied at leisure. As they were not governmental papers, Brodhead did not include them in the transcripts handed over to the New York State Library, nor did he mention them in his official report. Eventually, the Reformed Church in America obtained the so-called “Amsterdam Correspondence,” as Brodhead had hoped, although this acquisition required a substantial donation to the pension fund of the Amsterdam classis. The letters now form part of the collections of the Reformed Church in America held at the Gardner Sage Library of the Theological Seminary in New Brunswick.

With his trip to Amsterdam completed, Brodhead’s work in the Netherlands was done. In December 1841, he went to London to continue his search in the English State Papers. Unfortunately, it turned out to be difficult and timeconsuming to obtain access to the London archives. Brodhead also visited Paris on his hunt for history and while he was there a fire broke out at the Ministery of the Navy in The Hague. In an effort to save the seventeenth-century records, numerous papers were thrown out of the windows only to be scattered by a strong wind. Through intermediaries, Brodhead was able to acquire several partly scorched letters, written by seventeenth-century Dutch admirals and officials. These in turn made their way to America and are among the Brodhead Papers housed in the Rutgers University Special Collections.

The day after the fire at the Ministry of the Navy (1844)

Back to Brooklyn

Brodhead returned to New York in 1844 and spent several months compiling a calendar of the documents. He submitted his final report in February 1845, along with sixteen volumes of

transcriptions of Dutch documents, as well as the transcriptions of papers from London and Paris. It was a phenomenal achievement, considering the numerous constraints he faced in acquiring language skills, gaining access, arranging copies, and so forth. This collection formed the basis of eleven volumes of Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York (Albany: Weed, Parsons & Company, 1853-1861). Brodhead had hoped to translate and edit the transcriptions he had collected, but by this time the political landscape in Albany had changed and the job went to Edmund B. O’Callaghan instead. Brodhead decided to devote his time to writing a history of the state of New York. He completed two volumes, published in 1853 and 1871, that take the story of the state up to 1691.

John Romeyn Brodhead in his later years

Of course, John Romeyn Brodhead operated within the parameters and prejudices of his own time and did not challenge the conventions of the day. We cannot blame him for splitting up archival collections, as respect for the original order of archival collections was not considered important by scholars and archivists until much later. The accomplishments of John Romeyn Brodhead as a researcher and writer are undoubtedly considerable, nevertheless. He laid the foundation for a monumental publication that still serves as the first point of call for much historical research into New Netherland and New York.

Jaap Jacobs (PhD Leiden, 1999) is affiliated with the University of St Andrews. He is a historian of early American history, specifically on Dutch New York. He has taught at several universities in the Netherland, the United States and the United Kingdom. Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.

Jaap Jacobs (PhD Leiden, 1999) is affiliated with the University of St Andrews. He is a historian of early American history, specifically on Dutch New York. He has taught at several universities in the Netherland, the United States and the United Kingdom. Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.