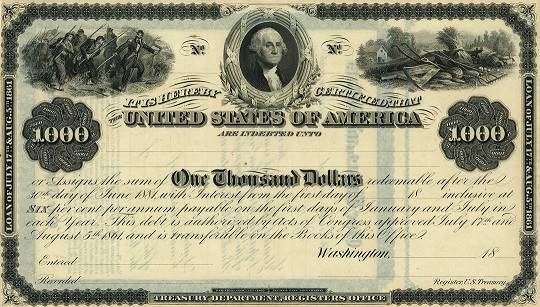

Following on the wild success of the 5-20 loan drive, the federal government attempted to maintain that success, but without one key person—Jay Cooke. When the question of an exclusive agency for the next major drive (the “10-40” loan, a 5% loan callable in ten years by the government that matured in forty), Jay Cooke did not initially receive the agency. Congressional investigations called for by both Democrats and Republicans to examine Cooke for war profiteering dogged Cooke throughout the 5-20 loan. While the investigations came to nothing, there emerged a great reluctance to bring Cooke once more into the fold.

Cooke’s absence from the 10-40 loan in conjunction with a 5% interest rate (versus the 6% of the 5-20 loan) dissuaded all forms of investors and the loan struggled to get off the ground. A new loan, the 7-30 loan, similarly struggled to take off in the absence of Cooke’s leadership. In the end, the federal government went back to Cooke with modified terms and he aggressively pursued the sale of US debt across the US.

Lincoln election banner 1864

The $830 million 7-30 loan issue ultimately became the most successful and most democratic issue of the war. With some 3,000 agents working on behalf of Cooke spread across the country, the loan made it into some of the most remote parts of the Union at that point in time. True, large sales took place in cities like Boston, New York City, Chicago, Cincinnati, and so on, but so too did sales take place in small towns across Maine, Iowa, Wisconsin, California, and Oregon. Such sales came at a very important and pivotal moment for the US government by the summer of 1864. By then, the Treasury struggled as it tried to meet the basic operating expenses of the war that were more than $2.5 million daily—a war of middling progress at this time it is worth noting. On August 17, 1864, the total sales of the 7-30 notes numbered some $17 million.

By the end of the year, however, sales had started to pick up among the masses, an achievement reiterated by President Abraham Lincoln in his 1864 Annual Address. “Held, as it is, for the most part by our own people,” Lincoln proclaimed, “[the public debt] has become a substantial branch of national, though private, property… Men readily perceive that they can not be much oppressed by a debt which they owe to themselves.” Central to this messaging and the success of the loan was none other than Jay Cooke.

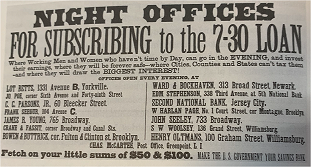

Cooke drastically expanded his marketing inspiration for the 7-30 loan. Utilizing a public relations firm out of New York City, various ads circulated in newspapers throughout the North reiterating a message of investing as a patriotic good and the power of confidence enjoined as one. Cooke also utilized entities referred to as night agencies. These operations located in major cities offered free coffee and donuts to those who were willing to listen to the merits of investing in the bonds. The offices specifically targeted those of the working classes who were either coming off or going on shift in the late night and early morning hours. Such types of methods of recruiting investors helped to demonstrate that advertising the war as one that drew financial support of the masses was not just a convenient marketing ploy, but rather reflected the realities on the ground.

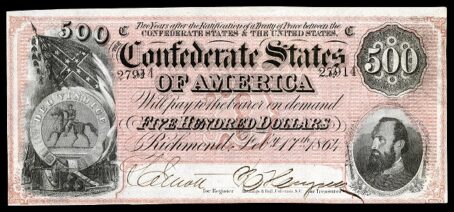

Sales even made their way into the Confederacy. As Union forces continued to push back Confederate armies in 1863 and 1864, the sale of bonds followed suit. Sizable operations emerged in localities like New Orleans (the largest city in the South) as well as throughout Virginia. Sales included not only local residents, free and formerly enslaved, but also local members of the Union Army.

Confederate money, 500 dollar bill

By the spring of 1865, the war started to come to an end and army operations and costs started to wind down. The assassination of President Lincoln led Cooke to personally manage debt sales in New York City to avert a financial panic. But the end of the war did not mean the end of the story of Civil War debt. For the end of the war inaugurated a new chapter in bond sales—thousands of miles away across the Atlantic.

David K. Thomson is an Associate Professor of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, USA. Thomson’s focus is on the financial history of the American Civil War era. His first book on the topic, Bonds of War, published by the University of North Carolina Press in April 2022 traces the crucially important role of bond sales by the United States government during the war to fund the conflict. Thomson’s work has also been featured in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Bloomberg. Click here for parts 1-3 of this blog series.

David K. Thomson is an Associate Professor of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, USA. Thomson’s focus is on the financial history of the American Civil War era. His first book on the topic, Bonds of War, published by the University of North Carolina Press in April 2022 traces the crucially important role of bond sales by the United States government during the war to fund the conflict. Thomson’s work has also been featured in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Bloomberg. Click here for parts 1-3 of this blog series.