Using a royal gift as a starting point, Jorrit Steehouder shows how ties between the United States and the Netherlands were forged through rituals and symbols, as well as through personal friendships.

On October 14th, 1947, a crisp and sunny autumn day, General Dwight D. Eisenhower celebrated his 57th birthday in style. At the Dutch embassy, in the heart of Washington, D.C., ambassador Eelco van Kleffens presented the legendary hero of World War II with an ‘honorary sabre’. It was not a conventional blade. Weighing nearly five pounds, the gold-encrusted sabre was embedded with hundreds of gemstones and had been meticulously handcrafted by one of the most skillful goldsmiths in The Netherlands: Brom’s Edelsmederij in Utrecht. In addition to its impressive appearance, the sabre surpassed the ordinary because it was a symbol of profound gratitude – from none other than the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina herself. The sabre’s scabbard was engraved with the words: ‘In grateful memory of the glorious liberation’. The blade itself was inscribed on both sides with ‘E pluribus unum’ and ‘Je maintiendrai’, the national mottos of the United States and The Netherlands.

The sabre was more than just a symbol of gratitude. Obviously, the liberation of The Netherlands by American forces (and indeed also Canadian and Polish) in May 1945 added a new layer to the already deep historical bond between the two countries. Wilhelmina’s gift harkened back to the existing ties, and, by celebrating the recent American sacrifice and valor, she helped to forge a lasting transatlantic bond of friendship between United States and The Netherlands. The sabre for Eisenhower, in that sense, symbolized the connection between two nations across the Atlantic in past and present, as well as in the future. Like the sabre itself, these connections were forged under pressure, particularly during and immediately after the war.

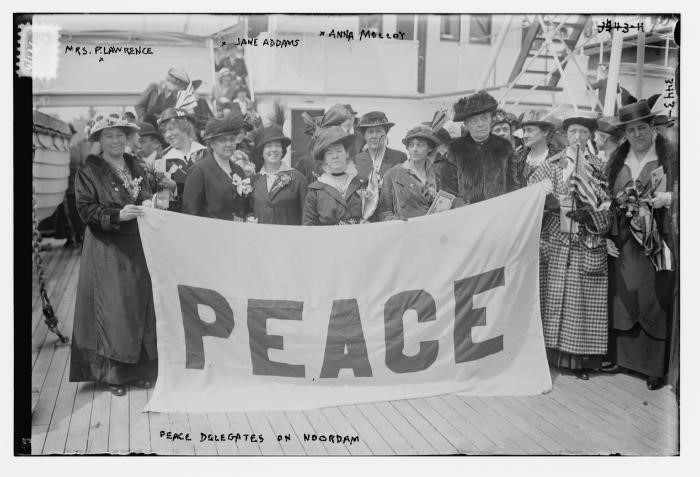

Eisenhower arriving in Amsterdam (Oct. 6, 1945). On the right is Prince Bernhard.

These were not all shiny celebrative moments. In fact, cementing lasting transatlantic bonds between The Netherlands and the United States entailed hard and painstaking work of diplomats, often out of the public gaze, going through piles and piles of paperwork and sometimes straining negotiations in backrooms, creating durable institutional and personal connections in the process. This was the job of men like Hans Hirschfeld and Ernst van der Beugel, who were stationed in Washington in the post-war years to explain to the American policymakers of the State Department why Europe needed post-war American economic assistance. Both the public and symbolic display of friendly relations (like gifting the sabre) and the laborious work of diplomats, however, are essential to forging durable relations.

Shortages of food and fuel

Forging Eisenhower’s sabre had taken well over a year. It was commissioned in July 1945, shortly after the end of the war in Europe. After a phase of planning, designing, and consulting between the brother-goldsmiths Jan Eloy Brom and Leo Brom, the Ministry of War, and Queen Wilhelmina herself, the processing of manufacturing the sabre could begin. There was even an effort at acquiring a better sense of what ‘Ike’ would appreciate in a sabre and how the makers could provide it with a personal touch that would befit the General. Most of the gemstones used for the sabre’s decoration had to be obtained, cut, and polished in France, which considering the large number, obviously took a long time. But there was another reason as well. As gas and coal remained rationed in The Netherlands during the immediate post-war years, the ovens required to heat the precious metals could not be used to their full capacity. In a sense, the making of Eisenhower’s honorary sabre went hand in hand with the gradual recovery of European industry and was plagued by the same bottlenecks that slowed Europe’s economic recovery: shortages of coal, oil, and food.

The Marshall Plan and the European reaction

In the months before Eisenhower was presented with the sabre, American policymakers were dealing with the issue of economic recovery, along with the shortages of fuel and food. In May 1947, Will Clayton, the Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs, had cautioned that without ‘prompt and substantial aid from the United States, economic, social and political disintegration will overwhelm Europe.’ Immediate action had to be taken to ‘save Europe from starvation and chaos,’ which could lead to a communist takeover. Clayton’s warning set the wheels of state in motion. Secretary of State George C. Marshall announced a large-scale program of economic assistance to European countries in a speech at Harvard University on 5 June 1947. Yet the Marshall Plan, as it became known later, did not resemble an actual plan yet. Many things were unclear: how would the Europeans receive aid, how would it be administered, how much would it amount to. And Congress of course had the final say. Instead of providing specifics, Marshall called on the Europeans to provide ways through which the American government could help them with economic recovery. In the words of Marshall, this was the ‘business of the Europeans.’

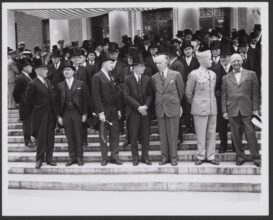

George C. Marshall on the steps of Widener Memorial Library, Harvard University, June 5, 1947

In the months following Marshall’s speech, European diplomats congregated in Paris to set up the Committee for European Economic Cooperation (CEEC). In essence, the committee was a standing conference, in session from July through October 1947. The sixteen potential European recipient countries of Marshall Aid first had to compile adequate information on their basic economic needs and, second, had to propose a collective program that addressed Europe’s economic problems. The first point resulted in a lenghty wish list presented to the American government. But the U.S. had been rather vague and unspecific on the second point and did not go beyond stating a desire for ‘constructive plans’ regarding European ‘self-help’ and ‘mutual aid’. The intensifying Cold War made it difficult for the U.S. to impose its will on Europe or even to state its aims openly. Doing so would raise suspicions in socialist and communist circles in western European governments and also draw criticism from the Soviet Union. This is where the Dutch came in. The Dutch delegation in Paris played an important role in refining the specifications of the Marshall Plan and communicating them to other European countries.

The arrival of the Dutch delegation at the conference in Paris, July 12, 1947

Dutch diplomats interpreting American goals

The leader of the Dutch delegation, Hans Hirschfeld, turned out to be an excellent interpreter of ‘vague’ American demands. Good personal contacts between Dutch and American policymakers enabled Europeans, Hirschfeld in particular, to make sense of what the Americans meant with these ‘constructive plans’. Clayton had been quite clear in off-the-record meetings with his European counterparts in Paris, shedding the ambiguousness of his colleagues in Washington. He expected nothing less than the eventual creation of large European market based on the American model. Clayton knew that it was not realistic to expect the Europeans to set up a full-blown European economic federation at this stage, but Hirschfeld was a smart thinker and developed an actionable plan for intra-European payments that would bring Clayton’s eventual goal one step closer.

In proposing increased European currency convertibility, Hirschfeld was acting along the lines envisioned by Clayton and in the spirit of the American government’s ultimate ideas for an economically integrated European continent. In addition, Hirschfeld was an early advocate of German economic recovery in a European framework. This was something that the French resented, but the Americans considered it necessary for Europe’s recovery. Hirschfeld also fully grasped the urgency of the moment. To him the Marshall Plan presented a unique opportunity, not just for his own country, but for Europe as a whole. Failure to take further steps on the road towards European cooperation, he noted, would ‘promote a tendency to autarchy’, which ‘would mean that the countries of Europe would become more and more isolated from each other, as occurred at the end of the first world war’. By reminding his European colleagues of the social and economic chaos that haunted the continent in the interwar years, he deliberately struck an emotional chord.

Eventually, the Paris Conference referred Hirschfeld’s plan to a study group, because its purpose was beyond the conference’s mandate. Meanwhile, in Washington, Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett was concerned that the lists of economic requirements constrained European thinking to ‘self-help’. Or, in other words, it limited European economic planning to policies that stimulated integration and mutual help between its own economies, instead of furthering economic dependency on America. By late August, Washington became seriously worried about the Paris Conference and the pending European reaction to Secretary Marshall’s speech. The total sum for the ‘sixteen shopping lists’ amounted to a staggering $28 billion. This was considered unacceptable to the American public, and Hirschfeld acknowledged that even before the Americans voiced their objections. Clayton’s emphasis on ‘financial and multilateral arrangements’ to achieve European ‘self-help’ was also a cause of concern. Monetary multilateralism, as Hirschfeld had proposed, fell short of American ambitions and did not help to sell the Marshall Plan to the American public. The State Department sent George Kennan, one of their top diplomats to Paris to straighten things out. Kennan told the Europeans to shift their emphasis from the ‘long-run gains of European economic integration’ to the ‘more urgent short-run needs’. This would make the plan more acceptable to American public opinion. After all, American citizens could very well understand the needs of hungry Europeans.

Hirschfeld at the State Department

The context of the Marshall Plan and its European reception determined the setting in which the honorary sabre was presented to Eisenhower. Initially, the Dutch Ministry of War had opted for a military ceremony in Washington. Eisenhower, after all, was honored for his military achievements. He was clearly a military man and not a diplomat or politician. Yet on the appointed day the ceremony took on a different hue. The reception hosted by Van Kleffens, attended by many American dignitaries, transformed it into a diplomatic setting emphasizing the strong ties between the two countries. In view of the large-scale public relations campaign to ‘sell’ the Marshall Plan to the American voters, this was a sensible move. Expressing gratitude to a country in the midst of the ‘second act’ in the liberation of Europe, as it was dubbed, could potentially win over an American public skeptical of dispatching more aid to Europe.

A week before the ceremony Hirschfeld also arrived in Washington. He had boarded the Queen Mary in London to cross the Atlantic, together with American Congressional leaders who had been on a tour to acquaint themselves with the dire economic state of European countries, in particular Germany. Several representatives of the Committee for European Economic Cooperation also sailed on the Queen Mary, including the French Robert Marjolin, the British Frank Figgures, and Hirschfeld’s fellow Dutch citizen Ernst van der Beugel. The atmosphere aboard the Queen Mary had been very friendly, as some of the travelers later recalled. Hirschfeld was unable to attend the reception for Eisenhower, as he had to answer questions from American policymakers about the European response to Marshall’s speech. In a painstaking last-minute effort, and under considerable American pressure, the Europeans had reduced their request for aid to acceptable levels. The meetings between the American and European delegations in Washington had been very complex and technical, but in the end did help to convince American policymakers of the feasibility of the plan, as well as of European intentions regarding economic recovery and mutual aid.

Diplomats understanding each other

The intense months of negotiations in Paris and Washington had also been a process of rapprochement between American and European diplomats. In Paris, Hirschfeld had shown himself a listener, with a good ear for American intentions for Europe. This had enabled him to closely align the European policies of The Netherlands, such as intra-European payments and German recovery, with American aims. On a personal level, he understood the difficulties the Americans faced. Hirschfeld knew it would be very difficult to sell the Marshall Plan to the American public, and that Europeans should be sensitive to the American domestic situation. Vice versa, American diplomats had gained a better understanding of Europe. Kennan had understood that there was a fine line between what the Americans expected from Europeans in the short run, and what they were prepared to do. Clayton had intimated to his colleagues that lowering the request for economic assistance had been ‘an extremely delicate matter of deep concern’ for Europeans, who could not be expected to accept lowered living standards for much longer.

Eisenhower holding the honorary sabre.

This episode in Dutch-American history shows that relations amount to more than what catches the public eye. Rituals, symbols, and expressions of gratitude certainly contribute to public perceptions of Dutch-American relationship, but do not fully explain the resilience of it. Dutch-American relations have been built on common history, as well as on common interests. In the case of the Marshall Plan, Dutch and American interests clearly aligned, and men like Hirschfeld and Clayton understood this. This gradual institutionalization of our countries’ relations makes them durable. It makes it possible to address difficult issues, such as the Dutch military interventions in Indonesia, starting in July 1947, a matter of deep concern to the United States.

Eisenhower’s sabre of honor remains in the collection of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas, where it is currently on display in an exhibition of the various tokens of gratitude Eisenhower received from all over the world for his role in the Allied victory in the Second World War. As such, it continues to symbolize the deep historical and emotional bonds between The Netherlands and the United States.

About the author

Jorrit Steehouder is Assistant Professor in the History of International Relations at Utrecht University. His research interests include the history of European integration, transatlantic relations, the history of exile communities during World War II, global multilateralism, and the history of Central- and Eastern Europe. He defended his PhD dissertation Constructing Europe: Blueprints for a New Monetary Order, 1919-1950 in January 2022 at Utrecht University.

Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.