Only six days after the surrender of the Confederate Army which meant an end to the Civil War, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Abraham Lincoln while attending Ford’s Theatre in Washington DC on April 14, 1865. As the news spread, the first reaction of most Americans was disbelief and shock, which turned into grief once Lincoln’s death was confirmed. “It seemed as if the whole world had lost a dear, personal friend”, someone said.

Lincoln assassination (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

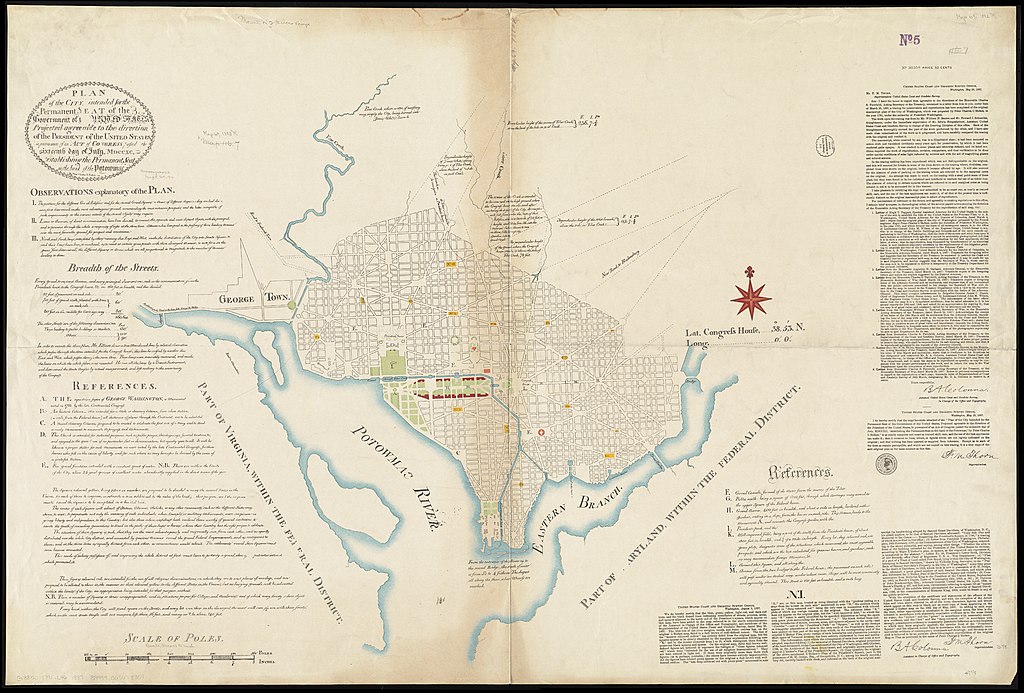

Congress’s plan to build a memorial to President Abraham Lincoln began in 1869, but due to endless squabbles (some things never change) about the design and location, Congress did not approve the actual construction until 1911. Two architects, John Russell Pope and Henry Bacon, were asked to put forward their designs. Pope’s proposals not only featured structures in the style of the ancient Greeks and Romans, but also an Egyptian-like pyramid, and a ziggurat, based on the stepped temple towers from ancient Mesopotamia (click here to see his designs). Ultimately, it was Bacon’s design inspired by the Parthenon at the Acropolis in Athens that got the green light. It seemed appropriate that a memorial to a man who defended the Union, freedom and democracy should be based on a structure located in the birthplace of democracy.

Ancient symbolism

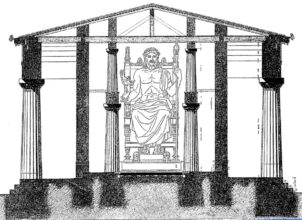

Zeus statue Olymypia (12 m) Wikimedia Commons

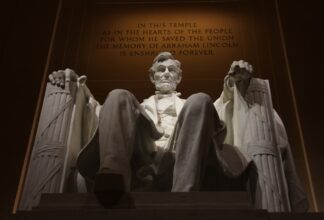

Aside from the Doric columns surrounding the memorial and its temple-like appearance, Bacon’s design is not a copy of the Parthenon. But it did draw on ancient symbolism. Walking up the steps, the colossal statue of Lincoln slowly reveals itself from within his marble home, leaving the visitors in awe. And although Lincoln might not have liked the comparison, it does make one think (whether consciously or unconsciously) of the grand statue of Zeus in Olympia.

There is another component of Lincoln’s statue that an ancient Roman would instantly recognize (although not interpret the same way): the arms of Lincoln’s classical marble chair are carved to resemble a bundle of wooden rods known as fasces. The history of this symbol is pretty dark: the rods bundled together with a leather strap were a handy tool for punishment in ancient times, or used as mere insignia carried around to install fear. It’s also where the word ‘fascism’ comes from.

Lincoln statue with fasces clearly visible

But in the Lincoln era, another interpretation was emphasized: a depiction of how individual sticks can be easily broken, but when bundled together, they could not. In other words, a message of unity and strength, carried by Lincoln, who fixed the broken Union which was now meant for the ages.

NEXT WEEK: Temple of justice. In part 5 of this blog series, we investigate the many ancient features of the US Supreme Court.

Mieke Bleeker works as event coordinator at the John Adams Institute. She holds a Master of Arts degree from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, where she studied Ancient History. Her fascination for the history and politics of the United States inspires her to visit the country regularly. She has written other blog series for the John Adams, about John Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry, and about the Pilgrim Fathers.