Eero Saarinen’s involvement in the modernist embassy program is a rare instance of continuity across a significant change of leadership in the Foreign Buildings Office that began under the Eisenhower administration. Saarinen’s design for Oslo exemplifies the International Style minimalism of the program in its early stages. His design for London demonstrates the shift towards contextual design. As such, these two buildings represent in microcosm the range of modernist designs produced by the US State Department during the Cold War.

Saarinen’s fenestration and the signature start-motif ceiling within (Oslo)

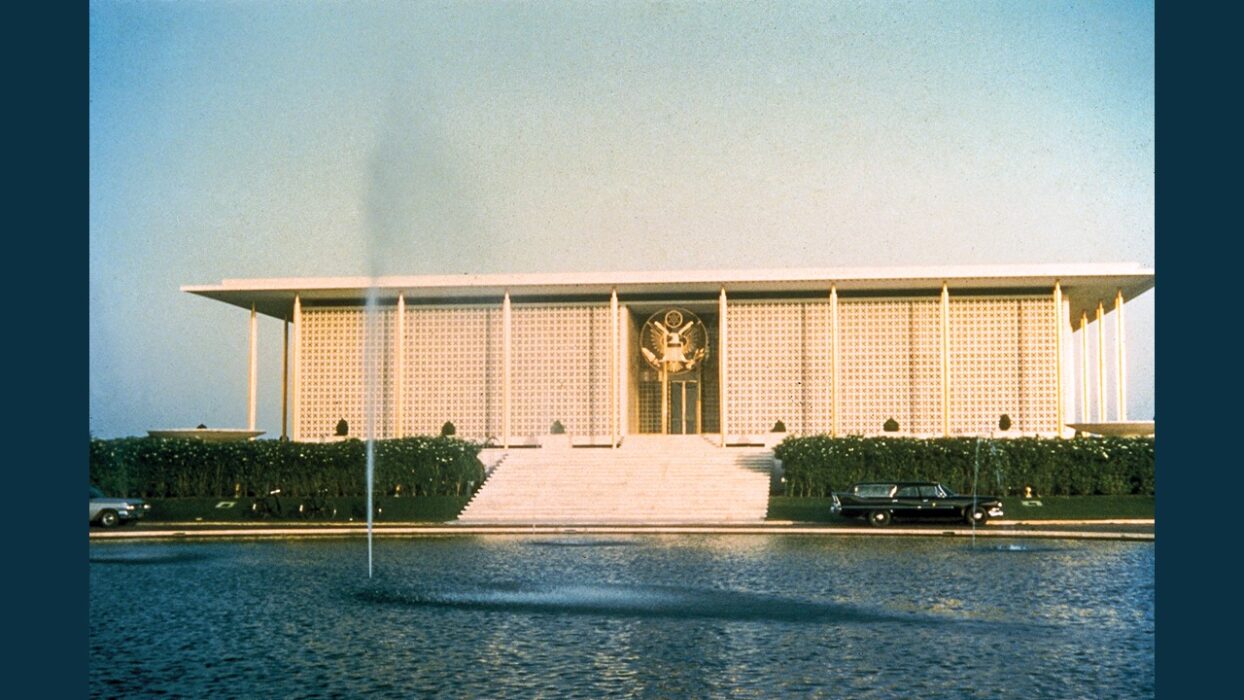

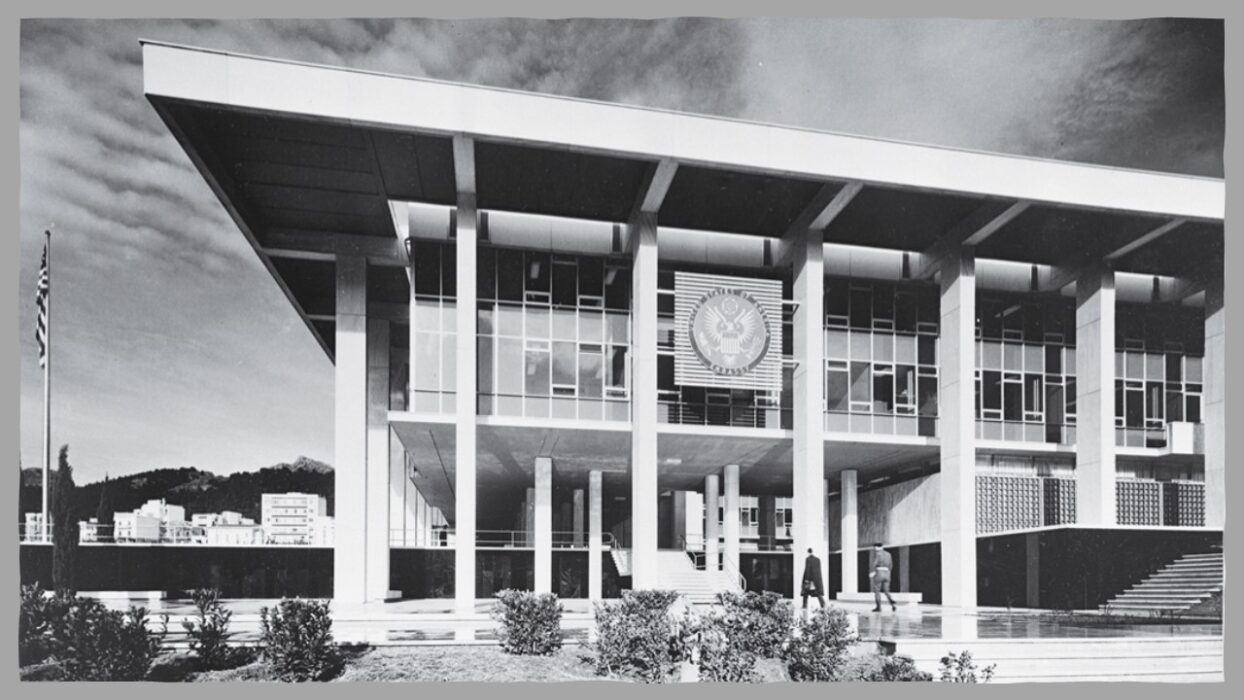

Although he described his design for Oslo as being inspired by a triangular Renaissance palazzo, in form, Saarinen’s embassy exhibits pure geometry: a restrained, triangular building with virtually no ornament. By contrast, his design for the embassy in London went to great lengths to appease the State Department’s Architectural Advisory Committee’s increased focus on contextual design. Whereas in Oslo the fenestration is tightly regulated, following an International Style grid akin to the Seagram Building in New York (and bearing no relation to its neighboring buildings), in London the fenestration was carefully harmonized to the proportions of the Georgian surroundings of Grosvenor Square. Likewise, in London Saarinen added a monumental gilded American eagle above the main entrance designed by Theodore Roszak, recalling a neoclassical pediment. Oslo features no such formalist touch.

Ironically, the efforts Saarinen undertook to appease the contextualist focus of the Architectural Advisory Committee resulted in an inverse response from the press. The design for the embassy in Oslo received widespread praise from critics. The State Department highlighted the embassy in its publicity blitz for the second round of new embassies in 1956, with Architectural Record highlighting the Oslo embassy alongside Sert’s design for Baghdad, Weese’s design for Accra, Neutra & Alexander’s design for Karachi, and others. In December of 1959, Architectural Forum heralded the arrival of “Norway’s Precast Palazzo,” describing the “rare polish” of Saarinen’s design, describing the embassy as “…a darkly handsome checkerboard of precast wall frames surfaced in a lustrous, greenish-black Norwegian granite.” The editorial continued, praising the Oslo embassy as a superior, more weightless design than his London embassy.

Architectural Forum’s preference for the Oslo design over its London counterpart is consistent with the broader critical reception for London, which created a storm of controversy and was broadly lambasted in the press. Critics took issue with the “jazz rhythms” of Saarinen’s fenestration, describing it as an unwelcome interruption to Mayfair’s broader Georgian melody. In the Times of London, the building’s new, bright white Portland stone façade was described as “tawdry,” and in The New Yorker, Lewis Mumford described the design as a “calculated insult.” In a State Department hearing on the Foreign Buildings Office, Representative Wayne Hays cast Saarinen’s entire building a “monstrosity.”

An art exhibition in the US embassy in London

Theodore Roszak’s 35-foot bronze eagle was an especially popular target of criticism, being broadly regarded as a deliberately offensive finishing touch. Member of Parliament Marcus Lipton called the eagle a “blatant monstrosity,” and both critics and ordinary Londoners characterized it as a gaudy and oppressive symbol of American overreach.

Other critics felt that Saarinen had not been bold enough, describing the building as too imitative and conservative, with the critic Peter Smithson puzzling why the architect accepted “such frozen and pompous forms as the true expression of a generous and egalitarian society.”

The current status of the two buildings reflects the critical reception they received upon completion. The Oslo embassy was awarded the silver medal of honor by the Architecture League of New York in 1960. Cited as “one of the foremost examples of international architecture in Oslo from the post-war years,” Saarinen’s Oslo embassy building was made a national landmark and came under preservation orders by the Norwegian Cultural Heritage Office when it was sold to Fredensborg AS, an investment firm, in 2017 for an estimated $44 million. The new US Embassy in Oslo, housed in a new, highly fortified, purpose-built compound in Makrellbekken, opened in 2017.

Lavish press coverage in Interior Design Magazine for the US embassy in London

Since 1956, architectural critics have mellowed in their view of the London embassy. Now hailed as a modern masterpiece, Saarinen’s embassy was designated as a Grade II listed building and benefits from certain protections under the Planning Act 1990. In the embassy’s designation report, Eero Saarinen is cited as an outstanding figure in twentieth century architecture and design, and his design for the London embassy is described as “an early example of a modernist yet contextual approach to design in a sensitive urban location. … Of particular note is the innovative application of the exposed concrete diagrid—an intelligent combination of structural expression and decorative motifs which provides cohesion to the whole and which illustrates Saarinen’s principles of marrying form to structure, interior to exterior—and his close involvement in details and execution.”

Despite this praise, the State Department sold the building to the Qatari Diar, a part of the Qatari Investment Authority for an estimated $600 million in 2009. David Chipperfield Architects is currently leading the project to reuse the building as a mixed-use development featuring a hotel, restaurants, and shops. This project has resulted in the demolition of the building’s interior while preserving Saarinen’s historic façade, raising serious questions about not only the appropriateness of a landmarked embassy building being converted into a private, for-profit enterprise, but also the meaning of “preservation” if the only feature preserved is the façade. The new, billion-dollar Kieran Timberlake-designed “ice cube” Embassy in London’s Nine Elms opened to overwhelmingly negative reviews in January of 2018.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.

David B. Peterson is CEO of Onera Group, Inc. and Executive Director of the Onera Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to supporting historic preservation. Mr. Peterson is Board Chair of the Harlem Academy school, an independent school offering students a leading education regardless of economic circumstance. He serves on the Advisory Council of the Glass House, a National Trust Historic site. He holds a BA from Dartmouth College, an MBA from NYU, and a MS in Historic Preservation from the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Click here to order ‘US Embassies of the Cold War’.