The work that historians do influences their lives, especially if they spend a considerable time in a foreign land that they write about. Slowly, their topic of choice becomes an essential part of their identity. Russell Shorto, a renowned writer of narrative history, writes about his own evolution at the intersection of Dutch-American history.

This blog concerns itself with the intersection of Dutch and American history. Previous posts have explored slavery in New Amsterdam, the naming – and renaming – of that city, and John Adams’ role as unofficial ambassador to the Netherlands during the American war of independence. As I pondered the task of contributing to that lineup, and scrolled through a mental list of possible topics, it occurred to me that, as I have lived at the intersection of Dutch and American history for more than twenty years, my own identity, and its evolution over that time, might be a relevant topic.

Once, after I gave a talk, someone asked me if I have a general approach to my books. I stalled a bit, trying to come up with an answer, then said something that, while vague, felt right. I said that I often start out at an intellectual place and end up at an emotional place. In terms of approaching a book subject, what I meant was that my typical entry point will be an idea, an under-appreciated aspect of history. Then, over the course of years spent researching and writing, as I eventually develop my own take on the subject, I become emotionally invested in it. The subject becomes part of who I am.

I might say something similar about my work at the intersection of Dutch and American history. I started out with an intellectual topic, and, over the years, my involvement has become deeply personal.

Children playing in the churchyard of St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery, 1994

Stuyvesant at St. Mark’s

I remember the moment my interest in New York’s Dutch roots was sparked. My daughter Anna (who is now in her twenties) was a toddler, and we lived in the East Village of New York City. The nearest open space for her to run around and play was the churchyard of St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery, on Second Avenue. The tombs of some of New York’s early inhabitants are there, flush with the ground. I liked the contrast of watching my vibrant young daughter play among the reminders of people long gone.

One of those tombs is that of Petrus Stuyvesant, the last director general of New Netherland and surely the colony’s most famous resident. I knew at the time that New York was once New Amsterdam, that there was a Dutch presence at the beginning, but I knew almost nothing else about it. It was my own ignorance that spurred me. I asked some historian friends what they knew about the Dutch period. They shook their heads. It seemed to be a black hole. Was there such a paucity of records?

Then someone suggested I contact Charles Gehring, who, it turned out, had been translating and publishing the records of the colony since 1974. (He is still at it, by the way.) I had three phone conversations with Charly, in which my sense of American colonial history was transformed. I began to realize not only that the Dutch contributed mightily to American history, but also that one could tell the early story of European settlement in America not just by looking at the Puritans and Pilgrims of New England, as had traditionally been done, but by focusing on Manhattan. And that would result in a very different trajectory. American history wouldn’t start out as Anglo-centric, for one thing. The Dutch colony was a multi-ethnic, polyglot place – one that more closely resembles not only New York today but the U.S. as a whole.

Russell Shorto (on the right) at the 2018 NNI conference on the Dutch roots of Brooklyn

Dutch Records

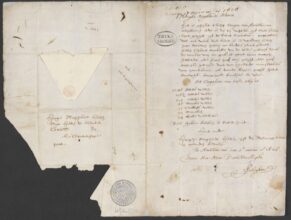

Far from being a black hole, New York’s Dutch period turns out to be rich in source material. The official records of the colony, which Gehring has been laboring on these many decades, comprise approximately 12,000 pages of material, and are located at the New York State Library and Archives, in Albany, New York. The National Archives of the Netherlands has many other notable documents from the period, including arguably the most important of all: a letter by a delegate to the Dutch States General who, in detailing the arrival of one of the first ships from Manhattan to the Dutch Republic, reports that the settlers “have purchased the Island Manhattes from the Indians for the value of 60 guilders.” Whatever deed was issued for that sale (which has gone down as one of the most infamous swindles in history) is lost, so this document amounts to New York’s birth certificate.

“Schaghen Letter,” 5 November, 1626

I spent so much time with Gehring and his collaborator, Janny Venema, that I eventually wrote a book about the Dutch colony and its Manhattan-based capital, The Island at the Center of the World, which became a bestseller in the U.S. What surprised me even more was that Dutch publishers vied for the rights to it. I had only been to the Netherlands on a couple of short visits; promoting the Dutch edition led to my first meaningful association with the country.

To Amsterdam

My next book, Descartes’ Bones, was about the French philosopher Rene Descartes, who spent much of his life in the Low Countries, so I decided to base myself in Amsterdam while researching it. I had originally thought to stay for a year, but then a friend, Tracy Metz, who was on the Board of the John Adams Institute, the American culture center in Amsterdam, told me the Institute would need a new director, and suggested I apply for the position. I did, got the job, and spent five and a half years at it. I thus found myself in the role of an unofficial bridge between Dutch and American cultures. Most of my work involved bringing prominent Americans – novelists, politicians, historians, scientists – to speak to Dutch audiences. Meanwhile, I would regularly field phone calls from Dutch journalists asking me to comment on current events in the U.S. And so I began not only to see the Netherlands and its history through American eyes, but, to some extent, to look at the U.S. from a Dutch perspective.

Russell Shorto and Tracy Metz at an event of the John Adams Institute (2021)

Not long after settling in in Amsterdam, I had a notion to write a history of that city. Following my pattern, I started with an intellectual idea – I would write about Amsterdam as a fulcrum of philosophical liberalism – but the book turned out to be quite personal. For one thing, I wove myself into it, not in a significant way, but rather to give the reader a stand-in, a tour guide. I began the book with me putting my then-infant son in the child seat of my bicycle and bringing the reader along as we rode through the streets of our Oud Zuid neighborhood to take him to daycare. I wanted to put enough of myself into the pages that the reader would feel he or she was accompanying me in the act of uncovering events and locales in the lives of Rembrandt van Rijn, Aletta Jacobs, Anne Frank, and other notable one-time residents.

Back to the US

I now live in the U.S., and hold a position at the New-York Historical Society, where, among other things, I focus on New York’s Dutch period. With the 400th anniversary of New Netherland approaching, I’m in regular communication with institutions in both countries as we plan talks, symposia, exhibitions, and the like.

Through the years, I’ve done hundreds of talks, videos, tours, TV and radio segments, and interviews. I floated through the canals with Jane Pauley and a film crew from the nationwide U.S. program CBS Sunday Morning. I gave the then-prince and princess of the Netherlands (now the king and queen) a tour of an exhibition at New York’s South Street Seaport Museum in commemoration of Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage, based on which the Dutch laid claim to the territory that became New York. As I say, when a writer interacts deeply with a subject, the subject becomes part of the writer, and that manifests itself in all sorts of ways. My son and my stepsons were born in Amsterdam; my daughters spent formative years there. My American wife lived in Amsterdam for 23 years. In identity, they all consider themselves to be somewhere on the Dutch-American spectrum. Even our dog is a Dutch-Frisian breed, a Stabijhoun, with a Frisian name to boot (“Friso”).

But what does it mean to stand at the intersection of these two nations and cultures? It means a hybrid language is spoken at our house. There are often stroopwafels and drop in the pantry. It means always having a perspective on – and a distance from – both cultures. It also means you never feel truly at home. Or, to put that in a more positive way, you always feel at home in two places at once.

Dutch and American

Then there is the history, the way it roots itself in one. What does “Dutch” mean? What does “American” mean? As soon as you try to define a national identity you become mired in contradictions and generalizations. But I think the effort is worthwhile: personally, because we all strive to understand ourselves, but also perhaps because the effort relates to larger things. Our respective societies, like most others today, are striving to come to terms with or understand or redefine their own identities. We are grappling with our past (or refusing to do so). To what extent does being Dutch, or American, make one complicit in historical wrongs? Is it liberating to push one’s society to own up to its past? Or is that misguidedly self-destructive? For those of us who feel it’s liberating, how do we do that work and still hold on to what we feel are positive values associated with the past? As a writer of history, I feel an obligation to maintain for myself, and to encourage my readers to develop, the knack of doing two seemingly contradictory things at the same time. You want to give people of the past some space; to allow for the fact that they lived in a different culture, whose values are not ours. And at the same time you want to critique them from what we today feel ought to be universal values. You need to cut them some slack for their sake, but also hold them accountable in such a way that we can process and move beyond the injustices of their age.

While I am an American, my close connection with the Netherlands and its history means that I feel these things, and grapple with them, from the Dutch side as well. Case in point: it seems to me that the Dutch long felt detached from America’s long, ugly history of enslavement. The stain of it was part of America’s history, America’s problem, not theirs.

But thanks to the work of scholars in the past few years we are coming to understand the Dutch role in developing the slave trade in what became New York. Jaap Jacobs has offered compelling evidence of the precise date that the first enslaved Africans arrived on Manhattan (August 29, 1627), and has detailed the circumstances behind their arrival. Dennis Maika has shown that the West India Company’s “experiment with a parcel of Negroes,” in 1659, marked beginnings of a serious trade in human beings in the future New York. Recent books by Andrea Mosterman and Nicole Maskiell have probed into the subject of slavery in New Netherland. Was it really, as past historians argued, less vile than it later became under the English?

Dutch Village in New York City during the Hudson commemoration (2009)

Another example. In 2019, the Amsterdam Museum struck a nerve in the Netherlands when it announced that it would no longer employ the term Golden Age to refer to the seventeenth century, on the grounds that that era of expansion and flourishing of art, science, and culture was only “golden” for a few, and that the golden hue came at the expense of countless others. The announcement caused an uproar in the Netherlands. I know Dutch people who felt that they were losing a piece of their history, almost as if their home had been broken into and a coveted keepsake had been stolen. The news made barely a stir in the U.S. But it went through me like a sword. I’ve lived and worked for so long in that age. Although I hadn’t been aware of it before, I felt a bit proprietary about the term. It was a part of my work; I’d employed the term countless times, as a matter of convenience, but also, it now occurred to me, with something like pride. As if, in connecting my American self to Dutch history, I had come subconsciously to feel that it applied to me in some way.

And then, nearly as surprisingly to me, I found myself agreeing with the Amsterdam Museum. I’m not sure if the change required effort on my part or if it happened as if on its own, but I suddenly saw the term in a new light: a distinctly less golden one. How golden did it feel to be a native of Ambon or Manhattan in the 17th century succumbing in bloody battle to Dutch forces? Or, for that matter, to be a Dutch soldier in those same encounters? There are legitimate arguments to be made in favor of maintaining the term. That era saw revolutions in art, science, political thought, and philosophy that, taken together, were unprecedented in history. Much of what we think of today as our modern selves comes from that time. I continue to believe that. But moving forward, for an individual as well as a society, sometimes requires stopping and staring at our presuppositions, seeing them from a fresh angle.

Zwarte Piet and Blackface

Another example is the ongoing debate over Zwarte Piet. When I first moved to the Netherlands, and saw the young men in blackface accompanying Sinterklaas in the streets, tossing pepernoten to children, I was utterly aghast. As an American in the 21st century, I had been raised to see blackface – which had been common among White entertainers in early 20th century America as a way of lampooning Blacks – as an abhorrent mark of racism. It stunned me at first that many Dutch people I knew seemed blind to it.

Sinterklaas Festival Day in Rhinebeck, upstate New York

Of course, when you grow up with something, it can take an act of will to see it anew. We all of us, in all cultures, are used to our cultural trappings. They make us feel comfortable. They reinforce that elusive but necessary notion: identity.

We are living in an age when many of our cultural presuppositions are being aggressively challenged. We’re being asked – or, it sometimes feels like, forced – to look at them anew. These bits of culture are so much a part of who we are that such challenges often feel like attacks on our very beings. No one knows how we will get through this period of upheaval. I like to think that my Dutch-American identity, if I can call it that, gives me some perspective. And perspective on ourselves, in times of upheaval, may be among the most valuable of human traits.

Russell Shorto is the author of seven works of narrative history, including The Island at the Center of the World and Amsterdam. He is the Director of the New Amsterdam Project at the New-York Historical Society and Senior Scholar at the New Netherland Institute in Albany, New York, and the former director of the John Adams Institute.

Russell Shorto is the author of seven works of narrative history, including The Island at the Center of the World and Amsterdam. He is the Director of the New Amsterdam Project at the New-York Historical Society and Senior Scholar at the New Netherland Institute in Albany, New York, and the former director of the John Adams Institute.

Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.