In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, two young travelers from Boston made trips to the Dutch Republic. One was from Boston stock, the other a Dutch New Yorker, born in Albany. They visited the same sites and wrote about their experiences, but their views are quite different.

In the eighteenth century, countless young British men went on Grand Tours to Europe as part of their cultural education. In elite circles, traveling was seen as an excellent way to become a more polished and gallant gentleman. As traveler Jonathan Belcher aptly put it, “a man without traveling is not altogether unlike a rough diamond, which is unpolished and without beauty.” Many travelers kept a journal to recount their experiences, either to themselves or to a home audience. Most such journals were penned by travelers from the British Isles, but the genre also reached the British colonies in North America. In 1704 and 1716, two young men from Boston, Jonathan Belcher and Jacob Wendell, wrote down their experiences of visiting the Dutch Republic. While their journals are similar in style and contents, they also reveal crucial differences in the writers’ personal histories. Compared, they provide us with a fascinating insight in Dutch-American connections in the early eighteenth century.

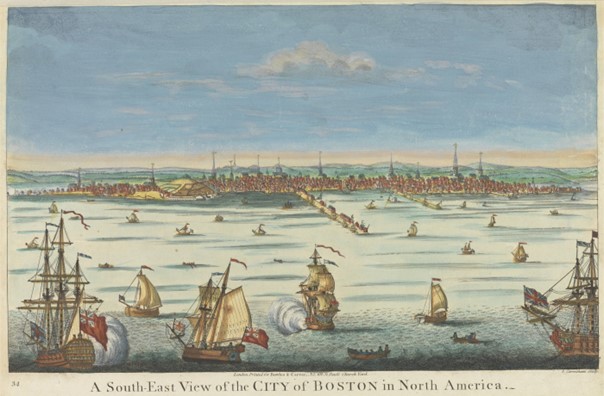

Boston in 1774. National Archives of the Netherlands

“A Poor Dutch Boy” in Boston

Jacob Wendell was born in August 1691 in Albany, New York, as the youngest of the eleven children of the Dutch couple Johannes Wendell and Elizabeth Staats. By the 1690s, Albany still had a large Dutch-speaking community, of whom the Wendells and the Staats were two of the wealthier families. Jacob’s family had mainly been engaged in the local fur trade, but the opportunities in that trade had been waning since the 1650s. Therefore, when Jacob came of age in early 1708, his family decided to send him to Boston to become a merchant’s apprentice. Apprenticeships in New England were becoming more common among mercantile families of Dutch descent. Boston in particular was an excellent place for young American-Dutch boys to familiarize themselves with British business practices, to learn the intricacies of polite culture, and to establish contacts with London trading houses. In addition, these young apprentices assisted their New York families in securing goods that were not readily available in New York City.

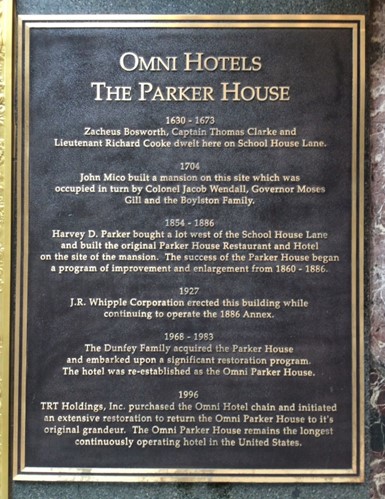

In 1708, Jacob arrived in Boston to work in the counting house of the Boston merchant John Mico. Though local legend has it that Wendell was just “a poor Dutch boy” upon arrival, he actually was well-endowed with goods to trade on the Boston markets for his family’s account. In addition, when he started to work under the auspices of John Mico his talent for business quickly began to flourish. Mico had arrived in Boston from England in 1686 as a factor for his London-based kinsmen Richard and Joseph Mico, and had established a trade in fish, ship masts, turpentine and tar. His headquarters were located in a mansion that became known as “Mico Mansion”, located on School Street just across King’s Chapel and the old Boston Latin School. On this location, where the Omni Parker House now stands, a memorial commemorates the history of the place and its previous owner (“Colonel Jacob Wendall”) who purchased the mansion after Mico’s death in 1718.

Plaque at Omni Hotels The Parker House, Boston

“The Hollander is Boorish to the Last Degree”

While apprenticing under Mico in the polite societies of Boston, it is highly likely that Wendell came across a widely circulated manuscript travelogue by the ambitious young Bostonian Jonathan Belcher, entitled A Journal of My Intended Voyage and Journey to Holland, Hannover, &c, July 8, 1704 to October 5, 1704. This lengthy journal recounted the Grand Tour Belcher had made in 1704 to the Dutch Republic and a number of German principalities. Jonathan Belcher was born in 1682 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Andrew Belcher and Sarah Gilbert. His father Andrew had begun his career as a modest tavern owner, but had gradually built a fortune as a shipping captain and merchant. In 1704, Andrew sent his son to Europe to strengthen their business contacts in London, Amsterdam, and Hamburg. The trip would allow his son to extend his horizons and further his refinement as a gentleman.

Once Belcher set foot in the Dutch Republic in July 1704, he at once displayed an incredible ability to find just the right connections to gain access to higher society. While visiting the States General in The Hague, he secured an appointment with the English ambassador James Stanhope (1673-1721), who connected him to Baron von Bothmer (1656-1732), the Hanoverian ambassador, who in turn wrote him a letter of introduction to the Hanoverian Court of Electress Sophia (1630-1709). With just two carefully arranged introductions, Belcher had gained access to the courts of one of the most influential principalities of Europe at the time. He kept a carefully composed and very extensive journal of his impressions of these visits. Clearly, Belcher never intended his account to remain private. With his journal, he aimed to inform and educate his Bostonian public on the curiosities of Europe.

In general, Belcher was impressed with the “very neat, clean and pleasant” towns of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch as a people were “very well contrived for trade” and “a people of indefatigable diligence,” but at the same time they lacked the manners and refinement of Englishmen: “the Hollander is boorish to the last degree, no air in conversation, nor indeed will they talk with you unless about getting of money.” However, contacts with strangers like the Dutch were very valuable for an aspiring gentleman: “traveling forms man into a civil, courteous behavior, and by using him daily to new faces, takes off all manner of bluntness.” Belcher’s account is also rich in detail as he remarks on individual towns, objects, and experiences. In Delft (“a very pleasant town”) he visited William of Orange’s tomb in the Nieuwe Kerk, which was “done to admiration in fine marble”. In the same town, he also viewed the Prinsenhof “the palace, where the famous prince Nassau was murdered.” In Leiden (“a dull melancholy town”) he visited the university building (“an old brick building not spacious at all”), and its botanical garden (“pleasant enough”) and anatomy chamber full of curiosities, including an “Egyptian mummy”. In Amsterdam, he marveled at the myriad trading activities taking place on the Damrak and met up with his “priceless friend Mr. Van Schaick”. This was Levinius van Schaick (1661-1709), like Belcher born in North America. Levinius, the son of the New Netherland settler Goosen van Schaick, had returned to Amsterdam to conduct business for numerous New York Dutch merchant families, including the Wendells.

Although direct evidence is lacking, it is very likely that Jacob Wendell was familiar with Belcher’s adventures and journal. The aforementioned Levinius van Schaick was just one of the many mutual acquaintances of the Belchers and the Wendells. Jacob himself arranged trade between the Belchers and Albany merchant John Schuyler (1668-1747), who was Jacob’s stepfather. Later in their careers, after Belcher had become Royal Governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 1729, Jacob and Jonathan most certainly knew each other personally. It was Belcher who promoted Wendell in 1732 to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the local artillery company, making him the “Colonel Jacob Wendall” as Jacob is still remembered as on the Omni Parker House memorial.

View of Boston, ca. 1720-1740, by J. Carwitham.

“My friends in Holland”

By 1714, when his apprenticeship with Mico was nearing its conclusion, Jacob Wendell decided not to return to his hometown in New York. In 1714, he had married into the influential Oliver family through his marriage with Sarah, the daughter of Cambridge physician James Oliver and Mercy Bradstreet. Now firmly rooted in Boston mercantile circles, Jacob permanently settled in Boston to establish his own merchant house. In 1715, he set sail for London to solidify links with the London branch of the Mico family, and establish new trading contacts. From London he arranged to visit his “friends in Holland” to “settle a thorough correspondence”. His choice of words resonates with Belcher’s concluding advice for future travelers and aspiring merchants: “if a man intends to live by trading and merchandize, traveling gives him the best opportunity to settle a correspondence in those parts of the world, where he may come.” If Jacob was aware of Belcher’s journal, he undoubtedly took this advice to heart.

By his “friends in Holland”, Jacob meant the family firm of the Haarlem textile merchant Albertus Hodshon (1661-1720). From at least the 1690s, Hodshon had been exporting textiles and other European manufactures to North America, where he traded with Dutch New York trading houses like the Van Cortlandts. Wendell was possibly introduced to Hodshon through a common New York City acquaintance prior to 1715, when he first received a shipment in Boston of Hodshon’s linens and textiles. Before they met in the Netherlands, however, they had never met in person.

When Jacob arrived in Rotterdam in early 1716, Albertus Hodshon had prepared everything carefully to make his Bostonian friend feel at home. He had sent his eldest son Theodorus to await him in Rotterdam and guide him to Haarlem, where he had prepared a room in his house, so that, as Jacob remarked, “I accepted of his friendship”. Hodshon had also arranged a sight-seeing tour to show Wendell the most worthwhile attractions in Holland. Together, they visited the Sint-Janskerk in Gouda, “in which church are the finest paints in the windows that are in all of Holland […] done by the brothers whose names were Wauter and Dirck Crabeth in 1555”. In Delft, they visited the Prinsenhof and saw “the place where Prince William I [of Orange, red.] was shut by a Spanjard just as he was coming down the stairs”, where “the marks of the bullets are yet in the wall”. In Leiden, he visited Leiden University and its botanical gardens, “where I saw trees that bore spices of all sorts, oranges and lemmons”. In The Hague, he visited the States General and the States of Holland, where he dined with “sundry colonels and officers of distinction, all Dutch”. The most in awe he was however by William of Orange’s tomb in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft, “on which he sits pictured out in solid brass”, which “was cast so often that it cost above 10000 sterling” and “is esteemed as fine a piece of work as is in the world.” Possibly with Belcher’s journal as an inspiration in mind, Jacob wrote his own sightseeing journal to recount his impressions of the Dutch Republic.

From “track scoot” to “treckscuit”

The contents of the sightseeing journals of Jacob and Jonathan were thereby quite similar, but there was one crucial difference that shaped their experiences: as an Albanian, Jacob actually spoke Dutch, and Jonathan did not. This undoubtedly made Jacob seem less foreign to the Dutch than Jonathan. Whereas Jonathan mentioned he was “altogether a stranger, & speaking no Dutch”, Jacob wrote that “I find my speaking of Dutch very advantageous to me while here, since not one in Mr. Hodshon’s family speaks English.” Indeed, with a Dutch term like trekschuit—a horse-drawn vessel used for passenger transport between towns —Jacob had considerably less difficulty (“treckscuit”) than Jonathan (“track scoot”). Whereas Belcher complained that “the Hollander” will “not talk with you unless about getting of money”, Jacob Wendell gladly noted he spoke with “many that would consign me goods”.

Belcher was of course a foreigner to the Dutch he met throughout his travels. Yet he aimed to highlight with his journal that a “civil, courteous” gentleman like himself could navigate foreign high society despite language barriers or other obstacles of foreignness. Jonathan aimed to show his Bostonian audience at home his talent to find and nurture just the right connections to get what he wants and needs. As such, his journey and journal are reflections of his personality, talents and ambitions. He already displays some traits of the tactful politician and diplomat who would later successfully lobby in Whitehall for the position of Royal Governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Wendell’s travel account is also a display of his personality and ambitions. He was first and foremost a merchant. His journal was barely a page long, almost hidden between the business correspondence on one of the final blank pages in the letterbook he had taken to Europe. Unlike Belcher, Wendell devoted no space to reflective remarks written with a Bostonian audience in mind. The account of his sightseeing tour seems to almost have come as an afterthought of what had mattered most for him in this journey: establishing “a thorough correspondence” with his “friends in Holland”.

Tomb of William the Silent, by Jan Luyken, 1730)

The Fruits of Dutchness

Jacob undoubtedly succeeded in his efforts. Over the next fifty years, he filled his mostly English letterbooks with an occasional Dutch letter addressed to the Hodshons and other Amsterdam merchant houses. The Hodshons’ goods allowed him to fill lucrative niches in the Boston markets. In December 1720, for instance, Wendell advertised in the Boston Gazette for Dutch linens “of the best sorts, just arrived from Holland”. Later in his career, he purchased his own ships for the journeys between Boston and Amsterdam, and gave them Dutch-themed names like Amsterdam and Prince of Orange. Though Boston had become his new home, Wendell never seems to have forgotten his Dutch roots in Albany, nor the “friends in Holland” he had established as a result of those roots.

Jonathan Belcher came to the Dutch Republic primarily for personal development. He sought to expose himself to foreign places and peoples to allow for enrichment and refinement of his character. For Jacob, there seems to have been no ulterior motives other than to establish and strengthen connections with people that must have felt comparatively close already. The spaces he visited were interesting and worthwhile of description in his journal, but he did not comment on the Dutch as a foreign, strange or “other” people, which Belcher did. The journal of Jacob Wendell’s visit to Holland shows how Dutch-speaking descendants of New Netherlanders could establish and nurture special connections between North America and the Dutch Republic, even from locations like Boston far beyond the former New Netherland borders. Of course, the journal of Belcher shows that Dutch New Yorkers were not the only ones capable thereof. Yet their ability to correspond in Dutch with Dutchmen was, as Wendell himself put it, “very advantageous”.

About the author

Sander Rooijakkers is a research master student in the History: Cities, Migration and Global Interdependence program at Leiden University. In the summer of 2023, as an intern for the Nationaal Archief, New Netherland Institute and New Holland Foundation, he worked on a preliminary survey of eighteenth-century Dutch manuscripts in repositories in New York City, Albany, Boston and Portsmouth. He is currently working on a thesis on Dutch Bostonian Jacob Wendell (1691-1761).

Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.