We will never know which ancestors of Nate Shaw were kidnapped in Africa and forcibly taken across the Atlantic, and when. But the first episode of enslavement in North America has been widely acknowledged in recent years. It was an English privateer, The White Lion, under a Dutch contract and sailing under a Dutch flag, that sold a cargo of twenty kidnapped Africans to the Jamestown colony in Virginia, in 1619, a year before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. A hijack letter signed by the mayor of Vlissingen gave a captain the right to attack and rob enemy ships—in this instance, the Portuguese São João Bautista—and thus to take hold of any captives on board. The Africans were subsequently exchanged for supplies and gold against “the best possible price.”

Slave auction in New Amsterdam (by Howard Pyle)

Within two years, fueled by visions of fortunes that could be made selling people, investors launched the Dutch West India Company. And within two centuries, a half-million Africans would disembark from Dutch ships in the West Indies and Dutch colonies on the Caribbean coast of South America. Coincidentally, the same number of Africans were brought to the continental United States on ships of all nationalities.

Today, “1619” is a battle-cry in the United States. The 1619 Project is the title of a best-selling book by Nikole Hannah-Jones that launched an acclaimed and frequently attacked public history project sponsored by The New York Times. Its major theme, simply put, is that the consequences of slavery and the infusion of black cultural genius belong at the center of the American national narrative. Tell me where you stand on 1619, and I’ll tell you who you are likely to vote for if you cast a ballot for President in 2024.

Which is to say that Hannah-Jones’s approach to interpreting the past and identifying 1619 as the starting year of the slave trade to North America has not been universally applauded. Critics chide it as an example of “displacement of historical understanding by ideology.” The 1619 Project’s greatest sin in their eyes is promoting the idea of the American Revolution as a war to preserve slavery. They oppose the notion that America was founded as a slavocracy and that current racial inequities descend from slavery. Their America was conceived in liberty and redeemed itself for all time through its founding principles. The Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, put the clash this way: “The question the 1619 Project posed was whether the American nation should be viewed as having its genesis not in the Declaration of Independence, with its covenants of equality and liberty, but in a commercial transaction for human flesh.”

May we claim both? Can we celebrate the Declaration of Independence and its ode to freedom and reason, while we mourn the deletion of the passage, composed in a moment of lucidity, that called racial slavery a “cruel war against nature itself”? Can we wonder how history would have unfolded had the country halted the transatlantic trade in human beings in 1776 instead of kicking the can down the road?

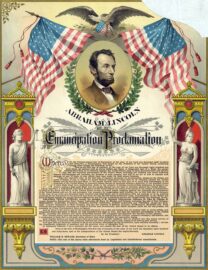

Emancipation Proclamation (Strobridge Lith Co.)

Emancipation of the enslaved in the rebellious states was decreed by President Lincoln in 1863—and not coincidentally in the Dutch West Indies that same year. In a peculiar reversal of custom, White southerners, smarting from their defeat in the Civil War, ceased to observe the July 4 commemoration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, while Black southerners, formerly enslaved, became obsessive observers. Still it would take two world wars and another eighty years for mainstream newspapers or school textbooks in the South to call black people Americans. Yet who could be more American than Nate Shaw, whose ancestors had been tilling the American soil for generations?

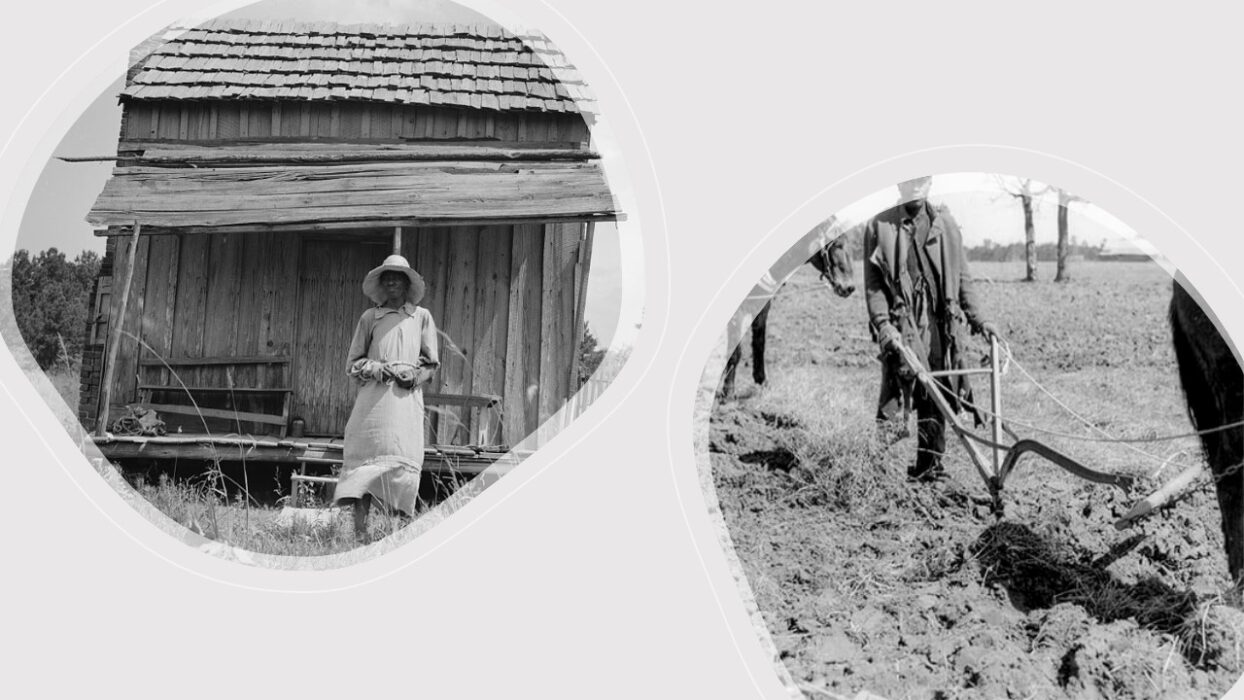

“I was born and raised here,” he explains, staking his claim to Tukabahchee County, to Alabama, to America. “I have sowed my labor into the earth and lived to reap only a part of it, not all that was mine by human right,” he continues. “I stays on if it gives ‘em satisfaction for me to leave, and I stays on because it is mine.”

There is no going back.

Next week we look at the issues that Nate Shaw faced as a cotton farmer.

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.