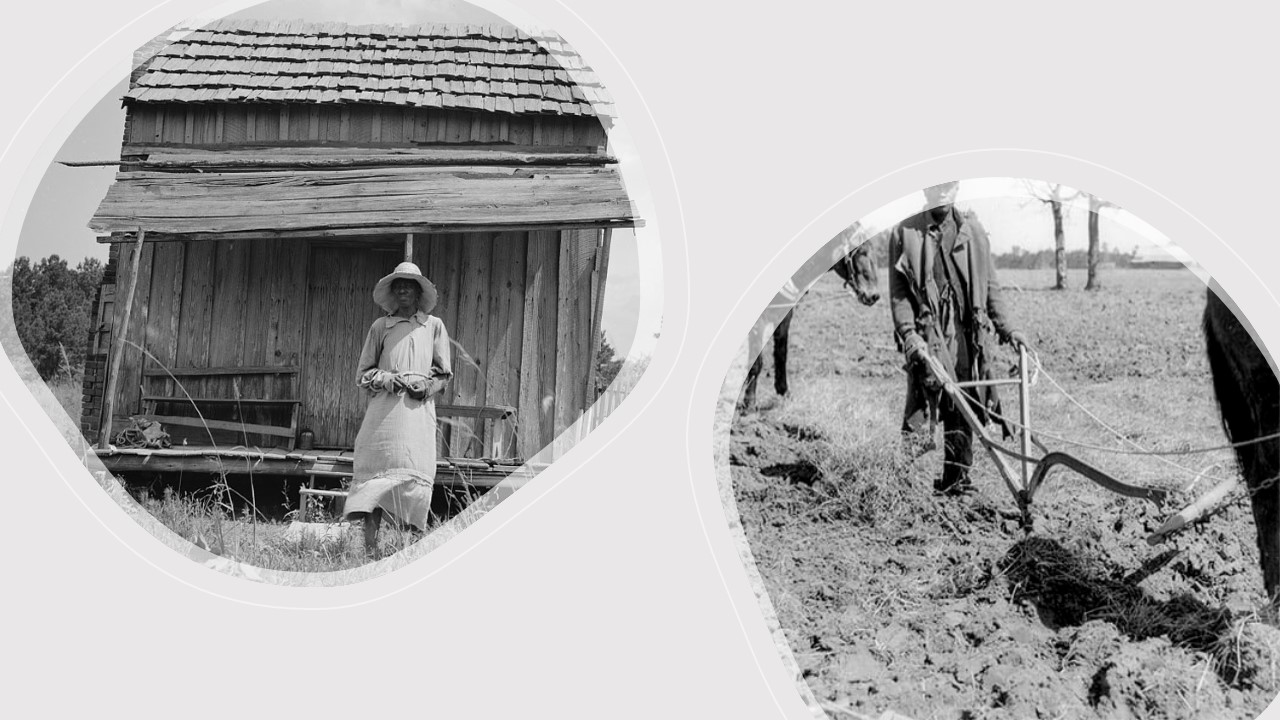

Following the American Civil War, landowners in the deep South did not want to pay for what they had always had for free—the labor of the people they had held in slavery. In cotton-growing states like Alabama, hundreds of thousands of freed people agreed to work on the land owned by their former masters in an arrangement known as sharecropping. In exchange for a mule for plowing, stipends of meat and groceries, and a cabin with a well, Black farm families received the proceeds from one-third of the crop. Seldom enough to pay their debts, let alone to accumulate savings to pass on to their children, the system tied sharecroppers to a cycle of poverty and entrapment.

Nate Shaw was an exception to the rule. For twenty-five years, aided by his wife, who unlike him could read and write, Shaw navigated his way through the system, avoiding catastrophic debt, enduring the disabilities and insults of racial segregation, and climbing the farm tenure ladder from sharecropping to renting to buying a homestead of his own. Then, one morning in December 1932, as a deputy sheriff came to seize his neighbor’s stock, Shaw packed his Smith and Wesson pistol in his belt and walked headlong into a fateful confrontation with the law.

Cotton pickers

Why did he do it, this man who had so much to lose—his life, land, livelihood, and the well-being of his wife and children? What motivated him to fight such an unequal fight? Did he believe he would be next? Was he tired of hearing the landlords squall “Bring me the cotton!”, usurping the growers’ right to sell their crop? Or was he moved by idealism and by loyalty to the trade union of predominantly Black farmers secretly organizing to improve their lives? Did he “step up,” as his middle daughter Mattie Jane put it, “to help his fellow man”?

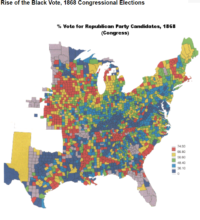

Nate Shaw was born in an age of counter-revolution, the white backlash to stop Black progress. He had heard his father, born in slavery, reminisce about the festive voting days when black people went to the polls, in the sweet decade of freedom that followed the Civil War. But then white people took over again and African-Americans were stopped from voting, by vigilante violence and Jim Crow laws. Young Nate was there when a deputy sheriff seized his father’s furniture and tools, even the mule’s harness. The counter-revolution was in full swing.

Nate Shaw was born in an age of counter-revolution, the white backlash to stop Black progress. He had heard his father, born in slavery, reminisce about the festive voting days when black people went to the polls, in the sweet decade of freedom that followed the Civil War. But then white people took over again and African-Americans were stopped from voting, by vigilante violence and Jim Crow laws. Young Nate was there when a deputy sheriff seized his father’s furniture and tools, even the mule’s harness. The counter-revolution was in full swing.

Nate was nine years old, in 1894, when his father put him to plowing. He had picked cotton in the fields since he was tall enough to reach the highest bolls, and now he was put in charge of a mule. Mules would be his close companions for the next four decades. Together, with the added labor of a growing family, they would produce bulky annual crops of cotton.

Make no mistake, the work was strenuous and punishing. It took three hoeings to chop away the tenacious grasses that rob nutrients from the shallow-rooted cotton plants and to thin-out the crop to “a stand.” In early summer came the first reward: the cotton flowers bloomed, the stamens released their pollen, and the plants self-pollinated. The petals turned from ivory to pink and fell to the ground, pushed by the bulging young cotton bolls that soon would burst open. To the farmer looking over his fields in late summer, no sight could match the beauty of the billowy sea of white.

African Americans using the cotton-gin (by W.L. Sheppard Harper’s weekly, 1869)

Problem was, it all had to be picked by hand. Francis, Nate’s third son, was having none of it. For him, the charms of rural life could not soften the tyranny of cotton. When the fiber blanketed the fields in the glorious “snows of southern summers,” Francis saw a vast desert of prickly fruit set to wage war on his body and soul. Years later, lugging an imaginary sack across his shoulder in the kitchen of his home in Philadelphia, he reached down as if to pluck a handful of fiber from a boll and implored heaven, “How much of this white shit does it take to fill a bag?”

Francis was lost to his father’s way of life. He revered Nate and marveled at the effort it took to raise nine children, ultimately to live on their own. But life beckoned the son in a different direction. Nate Shaw defended his property—his children’s doomed inheritance—unable to see that the battle already was lost. It was Shaw’s defeat and his victory, both, to paraphrase anthropologist Levi Vonk, that “only by breaking with the forms of his father” could the son honor what his father “strived toward most fervently.”

Next week we’ll fast forward to the present to address the issue of book banning and opposition to teaching Critical Race Theory (CRT), which currently embroils public education. Will All God’s Dangers escape the wrath of the censors?

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.