Gloria Wekker is an professor emeritus of Gender and Ethnicity at the University of Utrecht. In 2016 Duke University Press published White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race, about racism in the Netherlands. She is Surinamese-Dutch. At the Institute for War-, Holocaust- and Genocidestudies she spoke about the importance of an inclusive history. The occasion was the opening of the exhibition Black Liberators, about the Afro-American soldiers who helped liberate Western Europe during the Second World War.

©Lenny Oosterwijk

While reading the graphic novel Franklin: A Dutch Liberation Story, professor Wekker was struck by the general ignorance in the Netherlands on the topic of the children of black liberators. Is this a forgotten history, or a suppressed one, she wondered? There is an important difference between the two. A forgotten history has an accidental character, there was no deliberate attempt to ‘forget’ it.

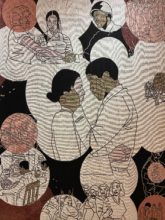

Tapestry depicting the history of African-American soldiers during World War II in the Netherlands. After drawings by Brian Elstak, designed by Lyanne Tonk and woven by FiberArt Pure Country Weavers.

However, the suppression of history is very intentional. It refers to hidden power structures. Who decides which questions are addressed in the discipline of history? Why has it taken until now until the history of these children of black liberators was written? It may be a cliché to say that history is written by the victors: but like most clichés it is also true. Ann Stoler, the Willy Brandt Distinguished University Professor of Anthropology and Historical Studies at The New School for Social Research in New York City, has coined the term colonial aphasia, which may be of use here.¹ Aphasia is a disorder which impairs a person’s ability to process language. Instead of talking about colonial amnesia, we should speak of the collective inability to speak. Colonial Aphasia is about 1. Actively cutting off knowledge, 2. The inability to create a vocabulary that connects appropriate words and terms with the corresponding things, and 3. The inability to understand the importance of that which has already been said.

Professor Wekker can speak about colonial aphasia from experience. When she was the Chair of the Diversity Commission at the University of Amsterdam in 2015-2016, many of the interviewed staff spoke openly of the lack of female professors and associate professors, but there was an incapacity to speak about religion and especially race and ethnicity. There was no vocabulary that allows the staff to speak out. Those who manage to speak on the topic, say: “with time, more teachers and students-of-color will come…” effectively placing the blame for their absence at the feet of the excluded groups.

Jonathan Israel – The Dutch Republic

Professor Wekker returns to history. She says that what she regards as the four canonical works on Dutch history, Israel, Schama, Shorto and Kennedy―all by foreign authors, coincidentally―have one fact in common: Race is conspicuously absent from their histories of the Netherlands. They reflect to the Dutch what they believe of themselves already and what they presumably have told these authors: we don’t do race, nor racism. And so, the issue of race in Dutch history is not forgotten, it is suppressed. Only now, it seems, has the time come where we can finally allow ourselves to look at the history of the black liberators and their children.

Tapestry depicting the history of African-American soldiers during World War II in the Netherlands. After drawings by Brian Elstak, designed by Lyanne Tonk and woven by FiberArt Pure Country Weavers.

If you have missed our previous two blogs, click here for my interview with Brian Elstak, the illustrator of Franklin – A Dutch Liberation Story. And click here for my interview with professor Kees Ribbens, about comics and popular history.

- Stoler, A.N. Colonial Aphasia: Race and Disabled Histories in France, Public Culture 23:1, 2011.