Monument Avenue was built as an extension of the city of Richmond in the late 19th century, and like many such projects, was at heart a real estate venture. But it was also an expression of the city beautiful movement inspired by European architecture, and echoed similar planning schemes like Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and Grand Army Plaza in New York. The concept of grand urban gestures has always been controversial, and as a photographer, I am particularly aware of the work of Charles Marville who documented the destruction of ancient Paris neighborhoods to make way for Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s boulevards and parks.

Jefferson Davis pavilion

Monument Avenue, however, did not slash through existing neighborhoods. It was a new spoke of the expanding city of Richmond, meant for upper class whites, and the perfect location for the Confederate memorials placed at intervals along its course. In northern cities, likewise, civic leaders erected monuments to Union generals, and in some cases, the same artists were employed. The now infamous Charlottesville Robert E. Lee sculpture was modeled by Henry Shrady, a New Yorker, who was also awarded the commission for the Ulysses S. Grant memorial in front of the Capitol in Washington, D.C., the nation’s most prominent monument to the preservation of the Union.

Detail Jefferson Davis pavilion

The critical difference, of course, was that Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, and the other Confederate luminaries were on the losing side. Typically, heroic statues in town squares are erected for victorious leaders, not the defeated leaders of a failed insurrection. But that is the perverse logic of the Lost Cause. That men like Lee were elevated in defeat. That the south went down with honor and dignity fighting for what they believed was right. Over several decades, statues to the south’s heroes went up by the dozens in front of courthouses and in public squares throughout the former Confederate states.

Detail Jefferson Davis pavilion

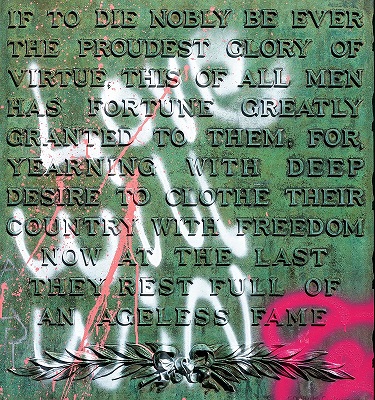

For me, all of this cognitive dissonance reaches its apotheosis in the Jefferson Davis memorial at the corner of Davis Avenue and Monument. A semi-circular colonnade surrounds a statue of Jefferson Davis standing, arm outstretched, beneath a fluted column topped with a female figure named Vindicatrix, goddess of vindication. On either side of him are plaques praising the bravery and sacrifice of the army and navy of the South: “Glory ineffable these, around their dear land wrapping, wrapt around themselves the purple mantle of death.”

Jefferson Davis had already been pulled down by protesters by the time I reached Richmond, and his pavilion was covered with graffiti, though not as florid as the Lee pedestal. A steady stream of visitors walked by, as they did the statue of Stonewall Jackson, the Confederate general, three blocks west. Jackson’s pedestal was splattered with paint almost obscuring the words: Born 1824 – Killed at Chancellorsville 1863. To be accurate, Jackson was wounded by friendly fire, and died some days later in a field hospital some distance away. But such is the power of the mythology of the Lost Cause. Herman Melville, the author of Moby Dick, and no sympathizer of the Confederacy wrote a poem in Jackson’s memory.

Statue Stonewall Jackson

Mortally Wounded at Chancellorsville

The Man who fiercest charged in fight,

Whose sword and prayer were long –

Stonewall!

Even him who stoutly stood for Wrong,

How can we praise? Yet coming days

Shall not forget him with this song.

Dead is the Man whose Cause is dead,

Vainly he died and set his seal –

Stonewall!

Earnest in error, as we feel;

True to the thing he deemed was due,

True as John Brown or steel.

Relentlessly he routed us;

But we relent, for he is low –

Stonewall!

Justly his fame we outlaw; so

We drop a tear on the bold Virginian’s bier,

Because no wreath we owe.

Detail Stonewall Jackson statue

It’s interesting to see in Melville’s poem the terrorist/abolitionist John Brown placed opposite Stonewall Jackson, the battlefield tactician and defender of slavery. Such complexity is, perhaps, more than I can handle in a series of pictures of statues. But what I did understand on the ground with my camera in Richmond, was that I needed to photograph these imposing monuments with sufficient gravitas, recognizing that their power was connected to their presence as art works and larger-than-life components of the urban landscape.

Click here for part 1 of this blog series.

Born in Virginia, Brian Rose moved to New York City in 1977 where he photographed the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and later participated in a survey of the Financial District, funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. Rose has since undertaken a number of long-term projects in Europe including documenting the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain, the rebuilding of Berlin, and the urban landscape of Amsterdam. In response to the election of Donald Trump in 2016, Rose photographed Atlantic City, the scene of Trump’s bankrupt casinos. He published a blog about this project for the John Adams Institute, called Atlantic City, Forlorn. Click here for his book about Monument Avenue in Richmond. Rose’s images have been collected by the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he has produced nine books.

National Endowment for the Arts. Rose has since undertaken a number of long-term projects in Europe including documenting the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain, the rebuilding of Berlin, and the urban landscape of Amsterdam. In response to the election of Donald Trump in 2016, Rose photographed Atlantic City, the scene of Trump’s bankrupt casinos. He published a blog about this project for the John Adams Institute, called Atlantic City, Forlorn. Click here for his book about Monument Avenue in Richmond. Rose’s images have been collected by the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he has produced nine books.