When John Adams arrived in the Dutch Republic as the American envoy, he was accompanied by his two sons. They were both expected to attend school so as to further their education, but finding the right place turned out to be a bit of a problem.

Johnny may have only been twelve years old, but this was the second time that the boy from Massachusetts had visited Europe. He was a studious lad, but could be stubborn, impatient, and a bit sensitive to criticism. Also, he did not want to travel to Europe again. He much preferred to go to a school in Massachusetts (and ultimately on to Harvard), but his mother had other ideas. So one Sunday afternoon after church she took him aside for a serious talk. According to her this was a unique opportunity for Johnny to “improve your understanding, for acquiring useful knowledge and virtue, such as to render you an ornament to society, an honour to your country, and a blessing to your parents.”

Statues of Johnny and his mother in Quincy (MA)

And so it was decided, and perhaps it was for the best. Johnny respected and revered his highly intelligent mother, certainly, but she had a sharp tongue and was quite severe. She considered rigorous discipline to be the main way of keeping her son on the straight and narrow. As a result, their relation was not particularly affectionate. In contrast, Johnny had a good rapport with his father. John senior could be irritable and impetuous in public, but in private he was largely easy-going. This did not mean, however, that he did not also insist on the best education for his son. Johnny was to study Latin, of course, as well as history, as learning about the past introduced one to both negative and positive examples of human behaviour. When Johnny was just ten, his father urged him to master Greek, “the most perfect of all human languages”, in order to read Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War in the original. Nevertheless, on reflection Johnny may have thought that another European trip was preferable to this onerous task. And so off he went again, this time in the company of his father, his younger brother Charles, and another relative, John Thaxter, who acted as his father’s private secretary and the boys’ tutor.

Sailing to Spain

The party set sail in the middle of November of 1779 and landed three weeks later at a port in Spain, much further south than had been the plan. It took them several weeks to travel northward until finally they reached Paris, their first stop. Their stay lasted only six months as having determined that his efforts to establish peace with Great Britain were not sufficiently supported by the French government, John Adams decided to change tack. Dutch support and recognition of American independence now became his objectives and he therefore took his sons out of their French school and traveled north in July 1780, the month Johnny turned thirteen. This time the destination was Amsterdam, which would surely, John thought, provide even better opportunities to further Johnny’s education. His mother, however, was more interested in character development. She expressed the hope that “the universal neatness and cleanliness” of the Dutch would cure Johnny of all his “slovenly tricks”, replacing them with “industery, oconomy [sic] and frugality.”

Upon arriving in Amsterdam, Adams, following the advice of burgomaster Hendrik Hooft, initially took lodgings at what today is considered the insalubrious Oudezijds Achterburgwal. Subsequently, however, they moved to the more upscale Keizersgracht 529, which now bears a plaque commemorating his stay. Adams immediately established contact with resident Americans and Dutch politicians and bankers, including Engelbert François van Berckel (brother of Pieter Johan van Berckel, the first Dutch Ambassador to the US) and Jean de Neufville, who would later finance land acquisition projects in America through the Holland Land Company. All of Adams’s contacts were patriotic, democratically inclined, in favor of American independence, and anti-British. In August, Johnny and Charles enjoyed several days of sightseeing in and around Amsterdam, including to a menagerie with “a lioness and a white monkey and several other beasts”, the Synagogue, the Admiralty, the botanical gardens, and several book shops. When the summer ended, it was back to school, this time at the famous Amsterdam Latin School on the Singel.

The Latin School in Amsterdam

Amsterdam Agony

Johnny hated it. He and his brother were what were known as “boarding scholars,” although they often spent Wednesdays and Saturdays at their father’s lodgings. But it wasn’t the separation from his father that displeased Johnny, or the nature of his companions. Rather, the rigidity of the curriculum did not permit his intellectual talents to flourish. The school provided special language lessons, but Johnny’s ignorance of Dutch meant that he was placed in the lowest class. As a result, his progress in other disciplines was poor. “Nothing remarkable today” became a frequent entry in his diary. Frustration began to creep in, followed by “disobedience and impertinence,” or so Rector Verheyk reported. He wrote to Johnny’s father asking him to take his son out of the school before his conduct necessitated meting out the treatment prescribed by the institution’s regulations. John Adams received the note with “surprise and grief” and requested that the Rector send his sons home that very evening, with their belongings to follow the next day. In a letter to his wife, John senior did not hold back in criticizing the state of education in Amsterdam, “where a littleness of soul is notorious. The masters are mean spirited writches [sic], pinching, kicking, and boxing the children upon every turn.” A month later, Johnny and his brother, accompanied by John Thaxter, made their way to Leiden.

Leiden was refreshing after the tedium of Amsterdam. It was Adams’s intention to have his sons stay in Leiden for some time so that they could “pursue their studies of Latin and Greek under the excellent masters, and there attend lectures of the celebrated professors in that university.” According to Adams it was “much cheaper there than here [i.e. Amsterdam]: the air is infinitely purer and the company and conversation is better. It is perhaps as learned an university as any in Europe.” An American student in Leiden, Benjamin Waterhouse, found his compatriots three furnished rooms at the house of the Willer family, located at Langebrug 45, within easy walking distance of the main university building. As his father reminded Johnny: “You are now at a university where many of the greatest men have received their education.”

The Academy at Leiden

Life in Leiden

Johnny loved it. He wrote to his mother: “I am now at the most celebrated university in Europe which was founded here for the valour of its inhabitants when it was besieg’d, when they were at war with Spain, it was put to its choice whether to be exempt from all taxes for a number of years, or to have an university founded here, and they wisely choose the latter.” Within weeks of their arrival, he and his brother officially matriculated at the university, and started to attend lectures. In addition they had three hours of daily instruction in Greek and Latin with a private tutor. Law and the Classics were Johnny’s daily fare, and he also began to teach himself Dutch by perusing newspapers. He soon declared to his father that he had read the fables of Phaedrus and the lives of distinguished men by Cornelius Nepos. Adams senior replied that he should move on to Demosthenes and Cicero. Indeed, during a visit to Leiden, father and son, joined by the Mennonite minister François Adriaen van der Kemp, met in the Golden Lion Inn where they discussed the moral benefits of reading Demosthenes. It goes without saying that this is not the kind of talk that is common amongst the students who frequent the Leiden bars today.

Fun and Games

There was time for other pursuits too. Johnny asked his father for a pair of riding breeches and boots, took long walks and, of course, attended church twice on Sundays. He also obtained permission to purchase skates. But skating was not just for pleasure, as John senior reminded him. It should be practiced in moderation and the aim was “not simple velocity or agility” but grace, which helped to teach self-restraint and moderation. Adams believed in self-improvement above all else. And he had another task for his son: Johnny was to inform himself “as perfectly as possible concerning the origin, the progress, the institutions, regulations, revenues et cetera of that celebrated university, and especially to remark everything in it, that may be imitated, in the universities of your own country.” John Adams was no doubt thinking of Harvard here. Johnny learned all that was expected of him and continued to delight in his intellectual pursuits. In short, he had the time of his life in Leiden.

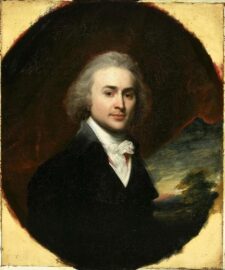

John Quincy Adams in 1796, by John Singleton Copley

Duty Calls

Sadly, these good times did not last. When the summer of 1781 approached, another opportunity offered itself. The new envoy of the United States to Russia was about to take up his post and needed a translator. As the main language at the imperial court was French, a language in which Johnny was fluent, he was the ideal candidate for the job. Just before his fourteenth birthday, therefore, Johnny went to St Petersburg and stayed for fourteen months. He regretted leaving Leiden and later in life considered the time in Russia a distraction from his intellectual development. Nevertheless, he would eventually return to the Netherlands in 1794. John Quincy Adams was appointed the US envoy there, following in the footsteps of his father. Though he was very reluctant to leave Massachusetts, his books, and his friends in Boston behind for his first diplomatic assignment, his duty to his country prevailed. It was the start of a public career that would eventually lead to the White House. Yet this elusive and almost inscrutable man, who constantly sought the company of books and would have preferred a life of letters, may never have been happier than when he was a young student in Leiden.

About the author

Jaap Jacobs (PhD Leiden, 1999) is affiliated with the University of St Andrews. He is a historian of early American history, specifically on Dutch New York. He has taught at several universities in the Netherland, the United States and the United Kingdom. Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other blog posts.

Jaap Jacobs (PhD Leiden, 1999) is affiliated with the University of St Andrews. He is a historian of early American history, specifically on Dutch New York. He has taught at several universities in the Netherland, the United States and the United Kingdom. Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other blog posts.