Stories handed down through the generations have a powerful impact. Alexandra van Dongen was always fascinated by the life of her American great-grandmother, an artist who eventually settled in the Netherlands. But Alexandra’s pursuit deepened when she unearthed her ancestor’s passion for an even earlier ancestor, whose actions in the nineteenth century speak to issues persisting in our times and makes for a story that she is keen to pass on to her own sons.

The American artist Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley (Perth Amboy, NJ 1860 – Rijsoord, Netherlands 1958), my great-grandmother, lived a long and interesting life. Her artistic career and family history has fascinated me since I was a young girl. Wilhelmina’s ancestors were English and Scottish migrants, who moved to the east coast of the United States and Canada in the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Wilhelmina was born on the 13th of July, 1860 in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, a small coastal town southwest of New York City. Her birthplace was a gable-fronted brick house at 213 High Street, built in 1854 in Greek Revival style by her grandfather George T. Merritt (St. John’s, Canada 1808 – Rome, Italy 1873). He was the wealthy editor-publisher of the Perth Amboy Journal and built the house for his oldest daughter Isabella. Merritt and his wife Jane Eliza Merritt-Milner (Ryde, Isle of Wight, UK 1810 – New York City, NY 1890) lived nearby, in a colonial brick mansion at what is now 225 High Street.

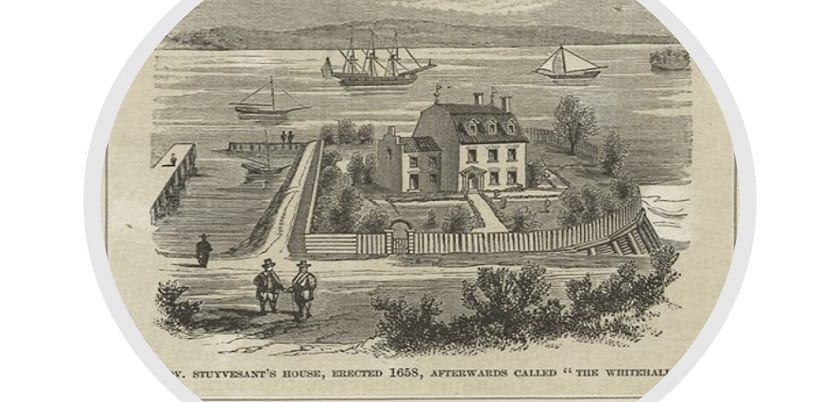

Birthplace of Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley

New York City: Never be discouraged

In 1879, at the age of nineteen, Wilhelmina enrolled in the Cooper Union Women’s Art School, one of the few New York academies open to female students. After one year, she continued her training at the Art Students League (ALS) in New York, a progressive art institution, which was founded in 1875 by a group of artists. While studying to become an artist, she was appointed as the librarian of the ALS. A few years later, Wilhelmina became the League’s first female vice-president. Her teachers and fellow board members included the artists William Merritt Chase, J. Alden Weir, Charles Yardley Turner, and Kenyon Cox. While in New York, Wilhelmina met many visiting international artists and writers. In 1882 the Art Students League was involved in the organization of the American lecture tour of the famous author Oscar Wilde. Wilhelmina’s diary shows that they met a number of times: “I had several long talks about books, art. etc. with Oscar Wilde.” She also accompanied him to a few artist studios.

In 1888, she jotted down the quote “Never be discouraged.” These were the reassuring words of visiting Russian painter Vasily Vassilievich Vereschagin (1842-1904) to Wilhelmina when she asked him what the first prerequisite of an artist should be. She was an active member of the New York Water Color Society, the New York Woman’s Art Club (National Association of Women Artists), the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy. This extensive network allowed her to take part in several exhibitions.

Paris: “For two years, or perhaps forever”

After spending the winter of 1892-1893 in Bermuda and breaking off her engagement with a mysterious Englishman, Wilhelmina moved to Paris on June 18th, 1892, “for two years, or perhaps forever,” as she wrote in her diary. At the age of 32, she sailed for Europe on the steamer Veendam (I). This was the second time she crossed the Atlantic, as Wilhelmina had joined her family on a European trip in 1872. Upon arrival in Paris Wilhelmina registered at the Académie Julian, one of the two private art academies in the city which admitted female and foreign art students. Yet she remained in the city for only a few days, because the academies were still closed due to the summer holidays. During her transatlantic voyage, Wilhelmina was accompanied by the Dutch-American artist John Vanderpoel (1857-1911) and his wife Jessie Elizabeth Humphreys (1869-1942). Vanderpoel, who was a well-known artist and taught at the Art Institute of Chicago (where Georgia O’Keeffe was one of his students), most likely advised Wilhelmina to spend the summer months at the charming village of Rijsoord near Dordrecht in the Netherlands, where he had founded an artists’ colony in 1886. A considerable number of international artists and art students from Paris flocked to Rijsoord during the summer months. In July 1892 Wilhelmina visited the artists’ colony for the first time. She would return often. During the winter months at the Académie Julian in Paris, Wilhelmina’s art teachers included the French artists Paul-Joseph Blanc (1846-1904), Pierre Fritel (1853-1942), Benjamin Constant (1845-1902), Louis-Auguste Giradot (1856-1933) and Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921). In her first year at the Académie Julian, Wilhelmina won the competition for the best composition in figure drawing, in which all male and female students took part.

Shortly before Wilhelmina’s arrival in Paris, the Canadian artist Laura Muntz (1860-1930) had arrived in the French capital in 1891 to take up her studies at the Academie Colarossi. Wilhelmina and Laura met there in 1893. Becoming close friends, they decided to share a studio building and living quarters on 111 Rue Notre-Dame-des Champs. Wilhelmina also posed for Laura several times. In the same year some of Wilhelmina’s artworks were selected for the annual Paris Salon. In addition, one of her Rijsoord paintings, Holland Peasant Girl, was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York. This was also the time when she met the American painter James Abbott McNeil Whistler (1834-1903), her neighbor in Paris. From 1892 onwards, Whistler lived in one of the studio buildings on Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, just across the street from Wilhelmina’s studio. According to our family tradition, Wilhelmina and Whistler became friends and regularly visited one anothers’ studios, where she also posed for him occasionally.

Rijsoord, the Netherlands

During the summer months between 1892-1900, Wilhelmina regularly traveled from Paris to the French countryside (Normandy and Southern France) and to the Netherlands. She returned to the artist village of Rijsoord many times, where she depicted the local villagers in many oil and watercolor paintings.

Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley, Mother and Child Sitting on the Grass, oil on canvas, Rijsoord, ca. 1892-1900

When Wilhelmina started teaching art classes at the Parisian Académie Colarossi, she took some of her international students to Rijsoord for summer schools. Rijsoord was ideally situated on an important European highway which connected Paris to The Hague. A local inn, dating back to the 17th century, on a beautiful spot near the river Waal served as a guesthouse to traveling artists. The old inn still stands today and now houses restaurant Ross Lovell. When Wilhelmina first visited Rijsoord in 1892, it was still called Hotel Warendorp. By this time small groups of mostly American art students from Paris visited the artists’ colony, sometimes accompanied by John Vanderpoel. In 1889 Vanderpoel’s cousin Volksje Noorlander-van Nes (1857-1933) and her husband Arie Noorlander (1843-1920) established a hostel called Pension Noorlander in Rijsoord, specifically aimed to provide accommodations to passing artists and art students. As the hostel was located nearby, the inn served as the lively summer headquarters of the artists’ colony during the summer months. The ground floor of the building comprised a living room, a dining room, and a room for drinking coffee. Most of the guest rooms were located on the ground and first floor. The visiting artists used a large space underneath the roof of the building on the first floor as a shared artist studio. Here they could dry their newly-painted canvases and water colors. When rain made it impossible to paint outside en plein air, the artists would work in the upstairs studio.

Bridge over the river Waal at Rijsoord. Hotel Warendorp to the right, ca. 1908-1912

In 1899, Wilhelmina apparently first encountered the 31-year-old Rijsoord farmer Bastiaan de Koning (1868-1954). They most likely met during a boat trip on the river Waal, as the story goes, as local villagers including De Koning, regularly rowed the artists to their outdoor painting locations. In the summer of 1900 Wilhelmina returned to Rijsoord again and announced her engagement to Bastiaan. They married a year later on December 5, 1901. Another three years later, when Wilhelmina was 44 years old, she gave birth to a daughter, my grandmother, Georgina Florence de Koning (1904-1973), named after Wilhelmina’s aunts. By that time, Wilhelmina had been active in the art world for twenty-five years. Family life did not prevent her from traveling abroad, visit exhibitions or meet her friends in Paris and New York. In 1915, her family in Rijsoord engaged a young housekeeper, Geertrui van Nielen (1895-1981), who became an important supporter in her life. Trui, or Troy, as she was called by Wilhelmina, took care of household matters and looked after Georgy, as Wilhelmina’s daughter was called, when her mother was traveling abroad. In 1930 Georgy married the Rotterdam-born Hans van Dongen. In 1933, at the age of 83, accompanied by her son-in-law Hans, Wilhelmina traveled once more to the United States to take care of family matters and to visit her brother Alan R. Hawley (1864-1938) in New York City, a stockbroker, balloonist and early aviator.

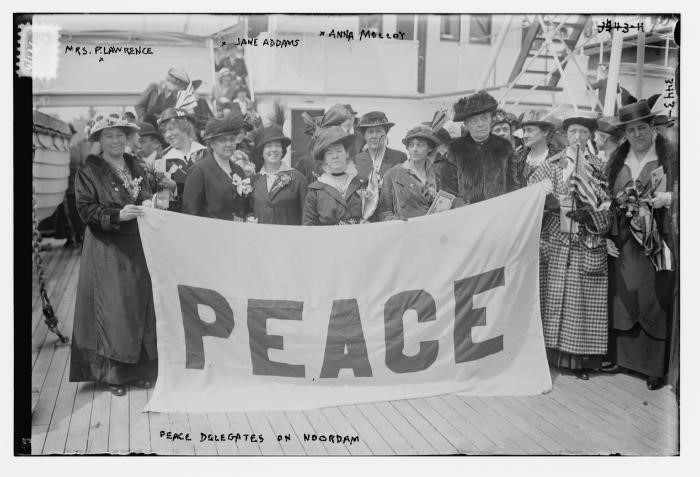

Washington DC

While in the United States, Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley and her son-in-law (my grandfather) Johan Casper (Hans) van Dongen (1907-1983), visited New York City, her birthplace Perth Amboy in New Jersey, as well as the nation’s capital. In Washington DC Wilhelmina proudly showed my grandfather the “Church of the Presidents,” St. John’s Episcopal Church at Lafayette Square, where her grandfather William Dickinson Hawley served as Rector from 1817-1845. He used to live in the church’s parish with his wife and children. The visit made a deep impression on my grandfather and made him eager to find out more about William Hawley’s personal and professional history. During his visit my grandfather decided to continue his career studying theology at Leiden University.

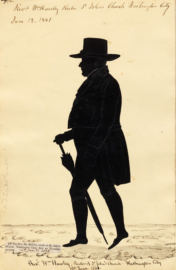

William Dickinson Hawley (Manchester, Vermont 1784 – Washington DC 1845)

In his book St. John’s Church, Lafayette Square. The History and Heritage of the Church of the Presidents (2009), historian Richard F. Grimmitt describes William Hawley’s interesting life’s story. Initially, Wilhelmina’s grandfather had chosen a career as a lawyer in New York City, studying under Judge Peter Radcliffe, a prominent attorney. But Hawley also had a strong interest in religious and civil rights matters. He served as a captain in the New York State Militia during the War of 1812, which many critics called “Mr. Madison’s War.” In June 1813, the governor of New York ordered the State Militia to prepare for a British invasion of New York. Subsequently Brigadier General Robert Bogardus, in charge of the Third Brigade of Infantry of the New York State Militia, subsequently issued an order to the commanders of units under his command. On June 10, 1813, Militia Captain William Hawley relayed the order to the company under his command, but added a statement critical of the Madison administration:

The United States being involved in war, whether just and necessary, we as citizens have a right to judge and to express that judgment without fear or molestation. But while we enjoy these rights, we are bound to render obedience to the laws of our country, and to support the Government, at the same time that we condemn the Administration for their weakness and folly in plunging us unprepared into this Quixotic war. From the support hitherto afforded the General Government by its citizens, we have a right to claim of them, and they are bound to give us protection. In consequence of the misconduct of our rulers, this protection has not been afforded us, and we are now called upon to protect ourselves. Painful as this duty may be, I hope and trust that every citizen under my command, will sacrifice with me, on the altar of patriotism, every feeling inconsistent with a full co-operation with the rest of our fellow-citizens; and when the enemy shall approach, to rally round the standard of our country, and in the defense of our liberties, our homes, and our fire-sides, be ready and willing to lay down our lives at the threshold of our country.

Hawley was arrested on June 19, 1813 for “unofficerlike conduct in endeavoring to excite dissention and insubordination among the company” under his command. The local press reported upon it in detail. Hawley admitted authorship of the order to his militia company and prepared a lengthy defense brief, outlining why he was not guilty of the crimes with which he was charged. The military tribunal denied Hawley permission to introduce this defense brief, but the major New York newspapers printed it in its entirety, taking up nearly an entire page in the New York Commercial Advertiser of July 30, 1813, and in the New York Everning Post of July 31, 1813. Hawley’s defense brief is an extraordinary document for its strong endorsement of the right of freedom of speech by citizen-soldiers, who served in a state militia not under the direct command of the president of the United States, as well as a strong criticism of the decision of the Madison administration to go to war with Great Britain when the United States was militarily unprepared to engage in such a war. At the conclusion of the proceedings, the military tribunal acquitted Captain Hawley of the charges against him without further comment. General Bogardus was outraged by the trial verdict and tried to annull the tribunal’s verdict of not guilty. Despite the wide publicity of Hawley’s trial in New York City, no further record of action against him by military authorities has been discovered sofar. Hawley subsequently resigned his captain’s commission.

Several months later, William Hawley became a candidate for Holy Orders in the Episcopal Church. He was ordained a deacon in the church by the Right Reverend James Hobart, the Episcopal Bishop of New York, in 1814. Thus he began his career as a minister. He soon left New York City for Virginia, taking up the position of Rector of St. Stephen’s Parish in Culpeper County, Virginia. Hawley’s appointment in May 1817 as Rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Washington DC kicked off his nearly twenty-eight-year leadership of the newly-built “Church of the Presidents” on Lafayette Square, just across from the White House. During those years, Hawley served four American presidents.

Auguste Edouart, ‘Silhouette of Rev. William Hawley’

A lesser known side of William Hawley’s life recently came to light in 2020, during the Black Lives Matter protests in Washington DC. As Rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church, Hawley baptized and married many African Americans of all legal statuses. Many of these marriages took place in Hawley’s own home, adjacent to the church, with his wife and family as witnesses. According to the marriage register of St. John’s, Hawley performed weddings for six couples identified as “slaves,” 38 identified as “colored” and two identified as “colored (free).” On January 11, 1828 for example, Hawley married Emmeline Matthews, listed as “colored,” to William Prates, listed as “slave.” When Hawley baptized and married parishioners’ slaves, their masters were at pains to explain to them that the ceremony had not endowed them with freedom in this world. Lafayette Square bears testimony to other aspects of slavery too. It was one of hundreds of sites in the United States where enslaved black people were sold during 250 years of slavery. The nation’s capitol was a major hub for the slave trade.

As the tobacco industry in the Upper South fell into decline, so did the need for large numbers of agricultural laborers, according to the White House Historical Association. Many slave owners decided to sell their enslaved workers to dealers based in Washington DC, who imprisoned them in crowded pens for weeks or months before selling them to the Deep South, where the cotton industry had expanded exponentially. Decatur House, which sits on the edge of Lafayette Square, is one of only a few remaining examples of slave quarters in an urban setting. Solomon Northup, author of the 1853 memoir Twelve Years a Slave, was a free black man living in New York before he traveled to DC, where he was kidnapped by slave traders in 1841 and sold into slavery. In 1852, abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) published her world-famous Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She was Wilhelmina Hawley’s cousin, four times removed.

In September 2020, abolitionist and church rector William Hawley was celebrated by Black Lives Matter activists and artists in Washington DC. They were invited by the current rector Rev. Robert Fisher, partnering with DowntownDC BID and the P.A.I.N.T.S. Institute (Providing Artists with Inspiration in Non-Traditional Settings), to create murals outside of the historic St. John’s church and the church’s parish house, to promote racial justice in response to the death of George Floyd at the hands of the police. The church’s parish house at 1525 H Street, NW once was home to Rev William Hawley and his family, who lived there from 1817-1845. Artist Demont Peekaso Pinder honored William Hawley with an extraordinary portrait painted on plywood, covering the parish front door. Next year I am planning to visit Washington DC again, this time accompanied by my twin sons Jonathan and Johannes Gaba, who were born in Rotterdam in 2001, in search for more information about our ancestors.

Demont Peekaso Pinder, Portrait of Rev. William D. Hawley, front door of St. John’s Church parish, Washington DC, 2020

About the author

Alexandra van Dongen (Leiden, 1961) is trained as a museologist (Reinwardt Academy) and art historian (Leiden University), and has been working at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam since 1986. Since 1992 she continued her career at the museum as curator of historic design, specializing in material objects as artists models. Her most recent publication is Dichter bij Vincent. Alledaagse gebruiksvoorwerpen in het werk van Vincent van Gogh. Alexandra is currently working on her forthcoming publication The Tangible World of Johannes Vermeer. Since 2018 she is involved in an ongoing research project about the history of colonialism and slavery of the city of Rotterdam. In 1995 she initiated and curated the traveling exhibition ‘One Man’s Trash is Another Man’s Treasure: The Metamorphosis of the European Utensil in the New World’, which reflected on the impact of European tradegoods on Native American culture.

Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States. Click here for the other parts.