The bonds that connect the American and Dutch peoples have been commemorated in various ways and at various levels. Dutch-American Friendship Day is a well-established annual event at the governmental level. In New York City, the historical memory of Petrus Stuyvesant has recently become controversial, but in the twentieth century his image was iconic.

Two hundred and forty years ago, on 19 April 1782, the Dutch States General decided to recognize John Adams as the envoy of the United States of America. It was the culmination of a contentious political process in which the Dutch Republic’s constituent provinces (Friesland being the first) instructed their delegates to vote in favor of accepting Adams’s nomination. With Adams in place as America’s minister plenipotentiary, the Dutch Republic reciprocated by naming Pieter Johan van Berckel as its first ambassador. Among his entourage were two young Dutch noblemen, Gijsbert Karel van Hogendorp and Carel de Vos van Steenwijk. After Van Berckel’s installation, Van Hogendorp and De Vos van Steenwijk toured the east coast of America, and turned their American sojourn into the New World equivalent of the European Grand Tour that formed an essential part of the education of elite young men. They were the first Dutch tourists to explore the newly founded United States of America.

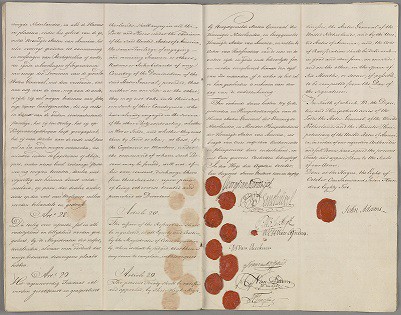

Treaty of friendship and trade between the US and the Dutch Republic. Signed on signed on 8 Oct,1782.

Dutch-American Friendship Day

Two hundred years later, in 1982, President Ronald Reagan officially proclaimed 19 April Dutch-American Friendship Day. Two centuries of diplomatic relations between the two countries constituted “the United States’ longest unbroken, peaceful relationship with any foreign country.” Every year the American Embassy in The Hague, the Dutch Embassy in Washington, and their respective Consulates in many other cities organize events to commemorate the Dutch-American friendship. These include civic receptions and the distribution of Dutch flowers. Annual events of this nature form part of the memory connecting us to the past, and add to the rich tapestry that represents and makes concrete a transcendent feeling of kinship shared by the Dutch and the American peoples.

Introduction of Pieter Johan van Berckel as the 1st Dutch ambassador to the US (31 Oct, 1783)

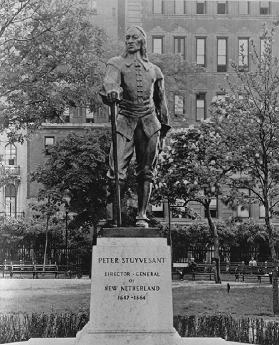

A Friendship Day is but one of many ways that keeps alive the shared history of the two countries. In addition, there are any number of annual events, statues, plaques and the like, all of which form part of Dutch-American historical memory. Commemorations are created intentionally, of course, and are based on specific motives and with particular aims in mind. These things evolve over time and this process is the topic of the present blog, which will focus on the historical memory of Petrus Stuyvesant in New York City, as embodied by a bust, an annual ball, and a statue. Stuyvesant, whose first name is usually anglicized as Peter, was Director General of New Netherland, the Dutch colony of which New Amsterdam, now New York City, was the capital. There is no doubt that he is an important figure in the early history of New York, not least because he was in charge for seventeen years. Over time, however, he came to represent much more. So much more, in fact, that in 1915 he was commemorated through the creation of a bust housed at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery in New York.

The Stuyvesant Bust

“Stuyvesant Kin Unveil Memorial,” the headline in the New York Tribune ran. “Bust Tribute Faces Altar at Spot Where Stern Warrior Knelt.” Other New York newspapers described the event in a similar vein. The New York Sun stated that: “All the speakers praised the character of the Dutch patriot and most of them declared that his sturdy patriotism had had a large part in the making of political New York, its government and its people.” Chevalier Van Rappard, the envoy representing the Dutch government, extolled Stuyvesant as “the founder of the principles of freedom, of tolerance and of appreciation of other man’s opinions, which at the actual moment still are the base of the American Constitution” and went on to declare him “the patron saint of New York.” General Leonard Wood, accepting the statue on behalf of the American people, insisted that “the spirit of Gov. Stuyvesant is the spirit of America.” The New York Times informed its readers that Stuyvesant’s effigy was a gift from Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government as a “token of goodwill.” In his acceptance speech on behalf of the Episcopal Church, New York’s Bishop David Hummell Greer emphasized Stuyvesant’s lasting effect on his community and said of the bust: “We shall always esteem it as a proof of affection between the two countries.”

Staunch seventeenth-century Calvinist that Stuyvesant was, he would have dismissed the patron saint epithet as “popish idolatry.” The anachronistic admiration he received on 5 December 1915 was not founded on nuanced or informed research. The Stuyvesant that was honored was a caricature, quite different from Washington Irving’s satirical image, but equally anachronistic. The lack of detail in the speeches underlines how little was actually known of the man behind the bronze bust. Instead, the speakers lionized an idealized image of boisterous, jingoistic leadership that was in vogue in the United States at the time, embodied by President Theodore Roosevelt’s style of government. While it made sense for a bust to be placed at St Mark’s, where Stuyvesant is buried, the question does arise as to why Stuyvesant was chosen at all. Where exactly did the idea to transform him into the symbol of Dutch-American friendship originate?

Bust of Stuyvesant

That is, of course, a long story, one that harkens back to the publication of Irving’s marvelous depiction of Dutch New York in 1809, in which “Stubborn Stuyvesant” featured prominently. A century later, the idea of presenting a Stuyvesant bust to New York City was conceived by Leonard C. Van Noppen, who at that time was the Queen Wilhelmina Lecturer in Dutch Literature and History at Columbia University. Inspired by the Hudson-Fulton Celebration of 1909, he had noted that there was no statue or bust of Stuyvesant in New York City and took up the cause. In June 1914 Van Noppen and Van Rappard persuaded the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs to put his weight behind it and things then began to move quickly. Within weeks government funds were made available and Toon Dupuis was selected to be the sculptor. The intended date for the unveiling of the bust was 13 October 1914, incorrectly thought to be Stuyvesant’s birthday. The First World War broke out, however, and plans ground to a halt. Funds for the Queen Wilhelmina Lectureship were now in danger of being taken away, which made Van Noppen all the more eager to push forward. Unfortunately, the unveiling of the bust and the concomitant media attention in December 1915 did not yield the desired financial result for Van Noppen, as the Lectureship was put on ice. It was resuscitated after the war and, like Stuyvesant’s bust, remains an important consequence of Dutch-American cultural relations.

Stuyvesant Square

In the 1930s, another Stuyvesant memorial was erected, only a few blocks north of St Mark’s. Again, there is a bit of history to this. In 1836, Peter Gerard Stuyvesant, a prominent New Yorker and descendant of Petrus, had transferred a parcel of land to the city, which was eventually turned into a park. The proposed name was Holland Square, but it was ultimately named after the donor of the land instead. By the 1930s the park needed an overhaul. The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation wanted to adorn Stuyvesant Square with a memorial of some sort and brought the matter to the attention of the Netherland-America Foundation which proposed the erection of a statue of Petrus Stuyvesant. In a memo, Harold de Wolf Fuller, the NAF’s executive director, asserted that a statue would be highly appropriate, as there was no other such memorial anywhere in the city. While the Parks Department would provide money for the pedestal, the NAF would supply funds for the statue.

The next step was to select a sculptor. In 1936, the Newark Ledger ran an article with the headline: “Mrs. Whitney to Fix Leg for Stuyvesant.” Another newspaper quipped: “Stuyvesant’s Peg Leg Puzzle to Sculptress.” The choice for a statue rather than a bust resulted in the question of whether Stuyvesant had lost his right leg or his left. The Netherland-America Foundation cautiously suggested that it might perhaps be the right leg, pointing to a Stuyvesant statue in the baptistery donated by three Stuyvesant siblings in 1924 to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Once the matter was resolved—it was indeed the right leg after all—the project came to fruition. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney researched Dutch clothing of the seventeenth century and her subsequent design received praise all around. The Stuyvesant statue was first exhibited at the Netherlands pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. At a luncheon in her honor, Gertrude Whitney called the statue “the embodiment of patriotism and civic pride”, which she considered of particular importance at that juncture in time, with war looming. Others praised Stuyvesant’s courage and steadfastness. Adriaan Barnouw, the Queen Wilhelmina Professor at Columbia University, declared that Stuyvesant had built the city into one of the finest in the New World: “It was a cosmopolitan town as early as 1664.”

Statue of Stuyvesant in New York

Unfortunately, the dedication of the statue in Stuyvesant Square turned out to be a dreary affair. June 4, 1941 was a rainy day in New York. In fact, the rain was so torrential that the speeches had to be moved indoors to St George’s Episcopal Church, located on the west side of Stuyvesant Park. Accepting the statue on behalf of the city, Newbold Morris, President of the New York City Council, praised the numerous attributes that New Yorkers had inherited from their Dutch ancestors. Thomas J. Watson, IBM-founder and chair of the board of directors of the Netherland-America Foundation, cited Stuyvesant’s success as a leader, for example. The statue was unveiled by Augustus Van Horne Stuyvesant Jr, a descendant of Petrus, and the last person to be buried in the Stuyvesant family vault under St-Mark’s thirteen years later. After the burial, the vault was sealed off and became inaccessible. Nevertheless it is said that the old Director General sometimes comes out at night to haunt his old stomping grounds.

A Multi-Layered Past

Thus the historical Stuyvesant became a canvas onto which the ideals of the 1910s and 1930s were projected. Today the name of the Stuyvesant family is no longer regarded as just “proof of affection between the two countries.” Another, darker, dimension has been added. Petrus Stuyvesant was an enslaver, like many others in New Amsterdam, and held approximately 15 to 25 Africans in bondage. The Director General’s part in the Dutch slave trade that laid the foundation for New York’s black community can no longer be overlooked, as it was in 1915 and 1941. As a consequence, the Netherland-America Foundation, instrumental in erecting the statue in Stuyvesant Square, quickly changed the name of its annual fundraiser, the elegant black-tie Peter Stuyvesant Ball, to the rather anodyne “NAF Ball.” Well-intentioned as the change undoubtedly was, the new name does nothing to acknowledge the Dutch role in the history of New York. In that respect, “The New Amsterdam Ball” would have served the NAF better.

It is easier to rename an annual event than it is to remove a material reminder of the past, however. By removing a specific memorial the memory of those who choose to commemorate that particular person or event is also erased. The City is a multi-layered palimpsest on which vestiges of the past have been inscribed by successive generations of New Yorkers who traversed the island of Manhattan and beyond. Would it not be better if it remained so as a reminder to today’s New Yorkers of their predecessors, people who can still receive admiration for their achievements as well as censure for their moral failings? If we, rightly, want to promote a balanced and inclusive sense of history, then erecting a new memorial would be appropriate. It would add to the rich history of New York City to commemorate a young African woman, Mayken van Angola, brought to Manhattan by the Dutch West India Company in 1627, who remained on the island until her death over six decades later. Mayken’s life will be the topic of the next installment of this series of blogs.

About the author

Jaap Jacobs (PhD Leiden, 1999) is affiliated with the University of St Andrews. He is a historian of early American history, specifically on Dutch New York. He has taught at several universities in the Netherland, the United States and the United Kingdom. Last year The Dutch National Archives commissioned historian Jaap Jacobs to produce a series of 24 blogposts, 12 written by himself and 12 by co-authors, on the 400 year relationship between the Netherlands and the United States.