Thoughts On Vietnam December 7, 2015

Jim Harris, United States Navy

Fittingly, I am writing this on Memorial Day. Surprisingly, thinking about Vietnam is harder than I thought. Vietnam was a growing, ominous spectacle for us in law school, but it was still a world away and surely would not amount to much. I opposed the war simply because I thought it was an arrogant use of America’s power devoted to no good end. It played no part in my commitment to serve. In 1966 I volunteered for the Navy’s JAG program. After I graduated and passed the bar in 1967, I went on active duty.

What I did not understand at the time was that the North Vietnamese were just as devoted to the freedom and union of their nation as America had ever been. Before partition into North and South in 1954, the Vietnamese had a thousand-year history of independence. They had fought the forces of colonialism since the middle of the 19th century and had utterly defeated the French at the battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954.

Our adopted classmate, Jim Wright, has written a new book called Those Who Have Borne The Battle. In it, he refers not to Vietnam, but to the war in Korea as “the missing chapter, the absent lesson in American military history.” We did not learn. In his review of Mr. Wright’s book in the New York Times Book Review of 27 May 2012, Andrew J. Bacevich concludes that “war was becoming amorphous – undeclared, lacking clear objectives, with victory as such no longer the goal.” Clearly, Korea was but a precursor to Vietnam.

Ho Chi Minh

The Vietnamese, of course, were not at all impressed by even so powerful a nation as America. They had waged active war against colonial powers since at least the 1920’s when a young Vietnamese nationalist, later known as Ho Chi Minh, was in the U.S. studying. He wrote letters to U.S. presidents asking for their help in ridding his country of French colonialism. They were ignored. American involvement began in earnest in 1965. It ended with our defeat in 1975. Vietnam remains Communist to this day.

Early in my active-duty years, 1967-1971, I was legal counsel to the Physical Disability Review Board at St. Albans Naval Hospital in New York. The board’s purpose was to meet with wounded sailors and marines, and to evaluate and to pass judgment on the degree of their disabilities. I remember learned discussions among the medicos as to exactly how much a twenty-year-old with only half a right hand or no legs below his knee would be worth the rest of his life. One young man had his forehead blown away, an involuntary pre-frontal lobotomy. He seemed only vaguely amused at the proceedings. Later, I was assigned to the trial team at Brooklyn Naval Station where I both prosecuted and defended errant sailors and marines who had run afoul of the Code of Military Justice.

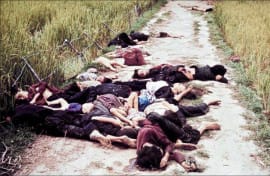

Victims of the My Lai massacre

As the war increased, I felt increasingly betrayed. For the first time, I realized that my government would lie to its citizens. There was General Westmoreland with his absurd search and destroy missions that turned out to be far more destroy than search. There was Cally’s slaughter of 104 civilians in a ditch at My Lai. There was McNamara, who now admits, with blood on his hands, “we were wrong, terribly wrong.”

Moments before this woman was killed by American military troops during the 1968 My Lai massacre.

And of course, there was Nixon, invading Laos, first with carpet-bombing. Then, he crossed the frontier of Laos with an invasion force of 600,000 U.S. and South Vietnamese troops, all the while loudly proclaiming “This is not an invasion of Laos.” This same Nixon also loudly proclaimed, “I am not a crook” as he decamped from the White House one step away from the Attorney General.There was the unholy alliance of Nixon and Kissinger who during peace talks conspired to bargain away men’s lives for the hope of political advantage.

When the war ended after ten years and more than 58,000 American deaths, plus another 350,000 wounded, I took comfort in one thought: At least we will never fight such a stupid war again. But that was before the war in Iraq.

Also read JAI director Tracy Metz’s introduction (December 2), editor Phillip C. Schaefer’s introduction (December 4), and the essay by veteran Glen Kendall (December 9), the essay by Karl F. Winkler (December 14), the essay by George J. Fesus (December 16), the essay by veteran Carl DuRei (December 18), and the essay by James Laughlin (December 21), the essay by John T. Lane (December 23), and the essay by Bud McGrath (December 27).