The Road from Dartmouth to Vietnam

U.S. Army, Medical Service Corps, December 23, 2015

Some things in life are controlled by our will, however I have found that very often one small, unplanned event creates an impact many years later. My road to Vietnam started with freshman year at Dartmouth. A senior living across the hall was recruiting freshman to fill the ROTC training unit. At the time I had no particular interest in the military and there was no economic incentive to join the Army ROTC unit. Nevertheless, when my hall-mate asked for help, I signed up.

Freshman year’s commitment to the military was minimal. I made friends in the program, consequently I continued with ROTC. I spent the summer of my junior year at officer basic training with students from all over the country. One name I never will forget is Cadet Mahar from the Citadel. He had a booming command voice and was the ultimate gung-ho cadet from a military school. I was to meet a much-changed Lt Mahar in Vietnam.

Upon graduation I received my commission in the Army Medical Service Corps. My initial posting was with the 82nd Airborne Division. Three months after I joined the division, the unit was deployed to the Dominican Republic. That nation was involved in a bloody civil conflict with significant Cuban involvement.

Vietnamese Navy boats laden with Vietnamese Army infantrymen swing along the Bien Tre river, July 11, 1967 (AP Photo).

Our division paid a high price. I vividly remember one aspect of the conflict. There was a temporary cease-fire in one sector of the city. At the time our rules of engagement prohibited any firing, except in return of hostile activity. One platoon was stationed across from a rebel position. The rebels reinforced their position and added a .50-caliber machine gun. The rebels then opened fire. One American was virtually cut in half by the machine gun. Four others in the sector received fatal injuries before the rebel position was silenced. I saw the remains of the carnage as the soldiers were evacuated through our medical channel. It was a life-changing event for me.

Three months later I received orders to join a hospital convalescent unit that was being sent to Vietnam. We were initially supposed to locate in Hue. Fortunately, wiser heads decided that Hue was too exposed and consequently our hospital avoided the heaviest fighting in the Tet offensive. Instead we were sent to Cam Rahn Bay,

My initial duty with the Convalescent Center was to supervise the shipment of all equipment and supplies from the US to Cam Rahn Bay. The transport was executed with a minimum of problems, however, when I arrived on station it was determined that certain items needed to be obtained from Saigon. I was sent to procure them, but when I arrived in Saigon no billet was available.

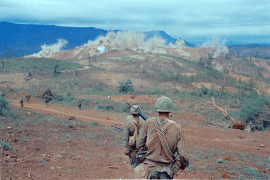

Air Cavalry troops taking part in Operation Pegasus are shown walking around and watching bombing on a far hill line at Lang Vei, April 14, 1968 (AP Photo).

My “Dartmouth” fate would take care of me. I decided to go to the US Armed Forces radio station in Saigon. It was my wild hope that the US Army had decided to put Al McKee’s Dartmouth WDCR experience to good use in Vietnam. When I arrived at the station Al was broadcasting. He took me to his billet for the evening. All went well until 2 a.m. when a major explosive was detonated at the front of the billet. We were not harmed but the lesson was clear. No place was safe in Vietnam.

When I returned to Cam Rahn Bay, work had begun on the site for the Convalescent Center. We were located on the ocean shore at the end of the airport runway. This gave additional security for the airport, as a significant number of our patients at any time were almost ready to rejoin their combat unit. The Convalescent Center, however, was exposed to attack from the sea.

There are many stories of patients that came through our facility. I would like to share two. The first is my renewed acquaintance with Cadet Mahar from the Citadel. He had become a seasoned infantry officer. Gone were the visions of glory, swagger and the confidence that American would easily prevail in Vietnam. His unit had seen extensive fighting in the highlands where the enemy and malaria had hardened his soul. He still believed the cause he fought for was right, but he knew the price he and his men had paid was very high.

John T. Lane

The second story is about PFC Battles. He was an inner-city school dropout from St. Louis. He had a minor problem with the law and was given the option of going to jail or joining the Army. Battles joined the Army and went to Vietnam. He fought the Vietcong and contracted malaria. I remember Battles because he was our first patient who had acquired a serious drug addiction problem in Vietnam. We cured his malaria, but I feared drug addiction would ultimately destroy him.

After eight months in Vietnam, my tour of duty was up and I rotated back to the US. Two months after I left, the VC came to Cam Rahn Bay by sea. The Convalescent Center and my friends were hit.

Also read JAI director Tracy Metz’s introduction (December 2), editor Phillip C. Schaefer’s introduction (December 4), the essay by veteran Jim Harris (December 7), the essay by veteran Glen Kendall (December 9), the essay by Karl F. Winkler (December 14), the essay by George J. Fesus (December 16), the essay by veteran Carl DuRei (December 18), the essay by James Laughlin (December 21), and the essay by Bud McGrath (December 27).