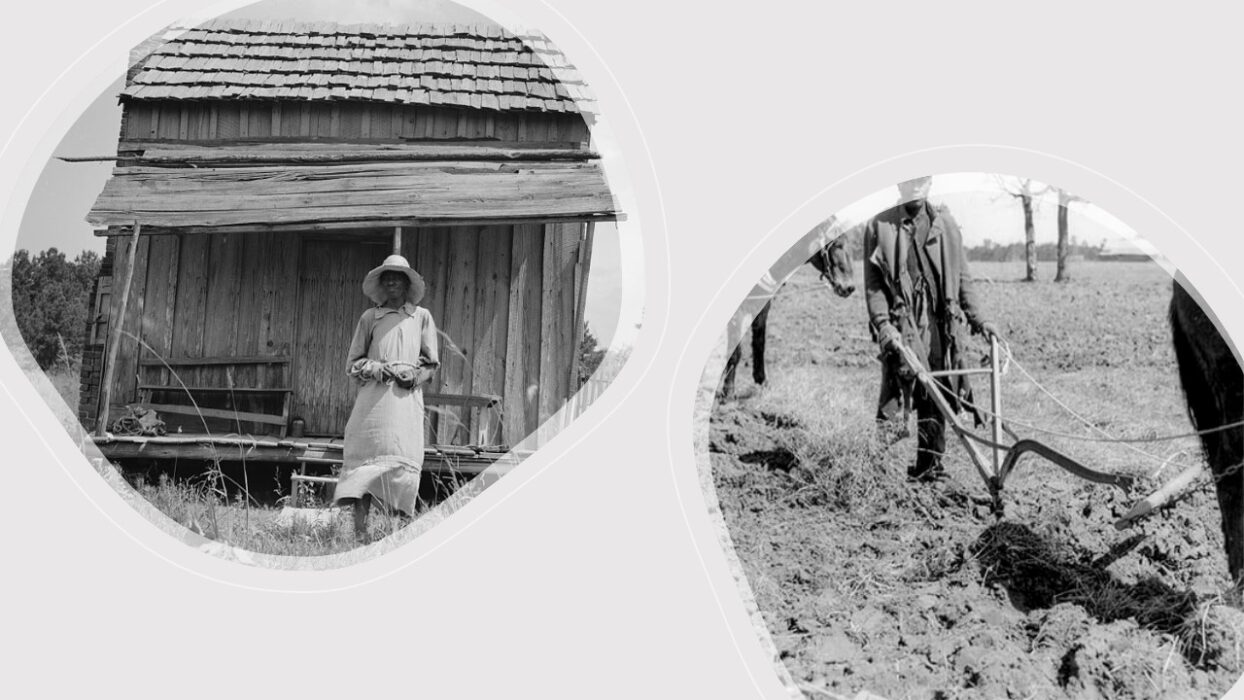

Children’s picture and chapter books make up thirty percent of banned books. In one fell swoop, a school district in Pennsylvania banished fifty books from lower and middle school grades on the grounds that the books’ donor “uses Marxist critical race theory.” A parent demurred, saying he had read some of the books and found no reference to Marxism. Several of the rejects are biographies of individuals the board found objectionable, such as the relentless advocate for Black empowerment Malcolm X, Black women including abolitionist Sojourner Truth, and, inexplicably, Bessie Coleman, the first black woman aviator, daughter of Mississippi sharecroppers.

Bessie Coleman (Collection of the Smithsonian NMAAHC)

Rejected were books about children coming to terms with their dark skin and naturally-coiled hair, books with titles like All Because You Matter, Hair Love, and I Am Enough, that exhort kids to love themselves and embrace their humanity. I Am Enough has been singled out by The Atlanta Voice, Georgia’s leading weekly Black newspaper, as one of the most requested books by Black teachers.

“The banning of one children’s book says it all,” wrote Brian G. in Cultured Magazine, referring to Love to Langston, a book of poems by Tony Medina that reflect on the renowned poet Langston Hughes, a leading voice in the Harlem Renaissance, a blossoming of Black literary life and a turning point in American cultural history. In 1926, when Jim Crow was riding high, Hughes had the courage, sensibility, and impudence to write, “I, too, sing America./ I am the darker brother./ They send me to eat in the kitchen/ when company comes./ But I laugh/ and eat well,/ and grow strong./ Tomorrow/ I’ll be at the table/ when company comes./ Nobody’ll dare/ say to me, eat in the kitchen’ . . .”

Amanda Gorman at President Biden’s inauguration

Joining Medina’s ode to Hughes on the restricted shelf of the elementary and middle school library is Amanda Gorman’s The Hill We Climb and Other Poems—named for the poem she famously recited at President Joe Biden’s inauguration in 2021. Gorman represents a new wave of Black writers whose fusion of art and activism are a threat, in her words, “to injustice, to inequality, to ignorance.” Consigned to the purgatory of banned books by a single complaint alleging that her work contains indirect hate speech meant to indoctrinate and not to educate, the appeasement by the school board of Miami Lakes in Florida shows how willing some people are to sacrifice their own children’s access to the nation’s cultural wealth. And for what? To turn around the Dutch slave ship that docked in Jamestown in 1619? To deny that Black history is American history and Black literature is American literature?

Toni Morrison’s name is near the top of every book banner’s list. No writer before Morrison, or since, has achieved more control over the representation of Black experience, or done so with language so driven by its content that it avoids the pitfalls of both convention and innovation. Her novel Beloved won the Pulitzer Prize in 1988. She was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama in 2012—three marks held against her by the right-wing Moms. Feared, envied, hated, misunderstood—and by some, understood only too well—Beloved has been removed from advanced course reading lists and libraries everywhere for its portrayal of enslavement, not the institution of slavery per se, but the inescapable traumas that once-enslaved people carried with them into freedom. White people are incidental to the story, hovering demons who, at any moment, “could take your whole self for anything that came to mind”—a characterization of relations between the races that eerily applies to All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw.

The word “beloved” was all Sethe, the protagonist of Morrison’s novel, could afford to have engraved on the tombstone of the infant daughter she killed to save her from living a life in bondage. Yet the infanticide that has so alarmed Morrison’s detractors co-exists in the novel with imperishable family bonds, a core lesson of tragedy’s defeat in Nate Shaw’s narrative as well. A dynamic of love and hate, forgiveness and revenge suffuses the two stories: Sethe and the ghost of Beloved, Nate and the specter of his father, Hayes Shaw, with whom he wrestled until his dying day. The son battled the father who had been born into slavery and carried forward the scars of servility.

Change may yet come for Sethe; change came once for Nate Shaw. Pain is its forerunner. “Maybe everything hurts,” wrote Amanda Gorman in Hymn for the Hurting. “Our hearts shadowed & strange./ But only when everything hurts/ may everything change.”

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Theodore Rosengarten is a writer, teacher, and social activist from McClellanville, South Carolina. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ted earned his bachelor’s degree from Amherst College and his PhD in The History of American Civilization from Harvard University. Even as a child, he was obsessed by the Black struggle for justice and freedom and by the Nazi’s destruction of the Jews in Europe. His first book, ‘All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw’, the oral history of a Black tenant farmer from Alabama, won the National Book Award for Contemporary Affairs in 1975. Last year, Yad Vashem Studies published Ted’s critical review of Steven T. Katz’s mammoth new volume, ‘The Holocaust and New World Slavery’.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.

Frans Kooymans, translator of Dutch to English and vice versa, has an American background. He emigrated in his early teens and lived in Ohio and northern Florida, where he encountered a society still marked by racial segregation. He spent five years in a seminary, taught Latin, then switched to become an accountant in Miami. Upon returning to the Netherlands, he continued in accounting and finance. A major company reorganization led him into his current profession. He calls the translation of Rosengarten’s ‘All God’s Dangers’ into ‘De kleur van katoen‘ his “covid project”.