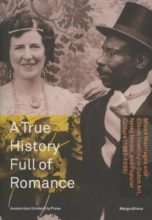

Marga Altena wrote the text for the graphic novel Franklin – Een Nederlands Bevrijdingsverhaal (Franklin – A Dutch Liberation Story). She is a cultural historian who publishes about class and ethnicity like the book A True History Full of Romance. Mixed Marriages and Ethnic Identity in Dutch Art, News Media and Popular Culture (1833-1955). The scenario for Franklin, her first non-fiction book, is based on her own research and studies like Cees van Kouwen’s Forgotten Liberators and Mieke Kirkels’ Children of Black Liberators. Marga is a project coordinator for Loving Day.nl, a platform for researchers and others interested in mixed race relationships and families in the Netherlands. As such, Loving Day facilitated and organized the Black Liberators project. Loving Day was named after the married couple Mildred and Richard Loving. You can watch the trailer for the movie based on their life.

How did Marga come to be interested in mixed-race couples and African American soldiers in World War II? “I was asked for this project because of my earlier work. For my PhD thesis, I studied how in the Netherlands about 1900, photos and films of female factory workers were employed by various producers to support very different political agendas. I discovered that there was a great likeness in the ways class and raciality were expressed. That’s why my thesis Visual Strategies was followed by my study of ethnicity in the Netherlands, resulting in the book A True History Full of Romance.”

© Brian Elstak

An important storyline in Franklin is how Frances, the granddaughter of the African American soldier Franklin, decides to find out who her grandfather was. She visits archives and searches online, looking for hints of her past. Was this a way for Marga to incorporate her research methods into the story she was writing? “Yes indeed. It was a way to show how historians do research, but my main object was to write a scenario about African American soldiers that would interest a large and varied public. It helps that Franklin includes several generations. For young readers it can be difficult to relate to people who lived 75 years ago. For them, it is easier to sympathize with a protagonist who they can imagine to be their grandfather. I hope that Franklin shows that this history still affects people’s lives today.”

The Black Liberators have long been a forgotten part of Dutch history. Why? Marga speaks from her own experience: “In Dutch research and in society the topic of raciality has long been avoided. I was told that researching racial issues in the Netherlands meant risking my career.” This is still a problem: When the Dutch news organization NOS covered our NIOD exhibition, their website received 900 negative reactions within 5 days. Comments dismissed NIOD, a respectable organization, as “a left-wing grachtengordel institution’ and the exhibition organizers as “out to divide the Netherlands.” Other comments stated that we are “forcing diversity into Dutch history” when we aim to fill a void in historiography and do justice to the Black Liberators. As a researcher, Marga studies patterns in people’s expressions and in media representations. If patterns of exclusion keep repeating themselves and prove to have long histories, you cannot but conclude that that the Dutch still have a problem with racism today.

In Franklin the children of the Black Liberators are highlighted. They were included to do justice to these children, and to show how history influences peoples’ lives today. The children of the Black Liberators were very visible in Dutch society at that time and they were considered a disgrace. Often, these children were sent away from their mothers and put in foster homes and institutions. There they were mistreated and sexually abused to such an extent that many were traumatized for life. As adults, they could only feel safe with their spouses and children; the rest of the world felt hostile.

Black Liberators Exhibition

Finally, I asked Marga how Franklin and the Black Liberators exhibition have been received by the public. At the exhibition at NIOD, like at the Vrijheidsmuseum in Groesbeek and at Theater aan het Vrijthof in Maastricht, visitor reactions have been very positive. Some of the visitors were children of Black Liberators themselves and they felt recognized and seen. Other visitors are surprised to learn about the existence of black soldiers in the Netherlands. Some wish to make them more visible in Dutch history, saying: “Every Dutch person should know this story!” The book sales for Franklin started slowly but are now picking up. And even more now the book has been selected as one of The Best Book Designs. Marga hopes that before long, Franklin will become widely popular and turn into a textbook classic. 100 copies are donated to school libraries to ensure that the story remains accessible in the future. Franklin – A Dutch Liberation Story is available at book shops, websites and through Rose Stories.

The first installment of our blog series was an interview with Brian Elstak, who created the art of Franklin. The second blog is an interview with NIOD researcher Kees Ribbens. The third blog is based on a talk by professor Gloria Wekker, about forgotten and suppressed history.