The namesake of this institute, John Adams, was unsurpassed among the American founders in the depth of his knowledge about politics, history, and law. No one in that age of remarkably learned political leaders – not even James Madison – read as voraciously or ranged as widely as Adams in contemplating the proper underpinnings of government.

John Adams, by Gilbert Stuart

One of the key insights that Adams gleaned from his studies was that republican government depended not just on the right institutions but also on the people’s character. No country could remain free for long, in his view, unless its citizens exhibited a sense of civic virtue – a willingness to put the public good ahead of their own – for otherwise politics would be little more than an insoluble clash of conflicting interests.

Yet Adams was never entirely persuaded that the American people possessed the requisite sense of duty. As early as January 1776, he fretted that “there is So much Rascallity, so much Venality and Corruption, so much Avarice and Ambition, such a Rage for Profit and Commerce among all Ranks and Degrees of Men even in America, that I sometimes doubt whether there is public Virtue enough to support a Republic.”

House of John Adams at the Keizersgracht, Amsterdam

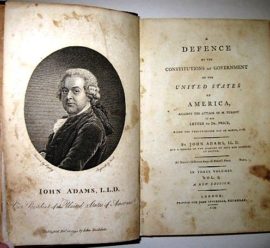

Adams spent most of the decade from 1778 to 1788 abroad, serving as a diplomat in France, Britain, and the Netherlands. Whereas the years that Thomas Jefferson spent as minister to France reinforced his belief in the unique purity of America and its people, Adams’s time in Europe had the opposite effect. In his magnum opus, the Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States, he declared flatly that “there is no special providence for Americans, and their nature is the same with that of others.”

Neither the launching of the new government in 1789 nor his own elevation to the presidency eight years later managed to assuage Adams’s worries. Just two months after his inauguration he grumbled that “the Want of Principle, in so many of our Citizens … is awfully ominous to our elective Government” and that “Avarice and Ambition … is too deeply rooted in the hearts and Education and Examples of our People ever to be eradicated.” It is doubtful that any other American president has been as pessimistic about the entire political order at the very outset of his administration.

After facing a challenging presidency and then losing a rather vicious election to Thomas Jefferson in 1800, Adams concluded that “downright corruption has spread & increased in America more than I had any knowledge or suspicion of” and predicted that “we shall be tossed … in the tempestuous sea of liberty for years to come & where the bark can land but in a political convulsion I cannot see.”

‘Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States’, by John Adams

Adams’s retirement lasted for more than twenty-five years – longer than that of any other American president until the twentieth century. During this period he experienced occasional bouts of relative optimism, such as in the midst of the patriotic fervor unleashed by the War of 1812. Throughout most of that quarter century, however, his bracingly candid and wonderfully colorful correspondence continued to dwell on his fellow Americans’ lack of fitness for republican government.

“Oh my country,” Adams exclaimed to his friend Benjamin Rush in 1806, “how I mourn over thy follies and Vices, thine ignorance and imbecillity, Thy contempt of Wisdom and Virtue and overweening Admiration of fools and Knaves!” To his son John Quincy, he predicted that “the Selfishness of our Countrymen is not only Serious but melancholly, foreboding ravages of Ambition and Avarice which never were exceeded on this Selfish Globe … the distemper in our Nation is so general, and so certainly incurable.”

In all, then, Adams’s disillusionment with the American experiment started much earlier than it did for the other protagonists of this series- before the Constitution was even a twinkle in the framers’ eyes – and lasted for nearly a half century. As he saw it, the pervasiveness of selfishness, avarice, and ambition would pose a perpetual threat to America’s fragile project of self-government.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here to read the first three parts of this blog series.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here to read the first three parts of this blog series.