Thomas Jefferson’s disillusionment was in many respects the most surprising of all. For most of his life he was consistently – one might even say relentlessly – optimistic about America’s future. Even when the Federalists implemented measures that he deemed deeply objectionable during their ascendancy in the 1790s, from Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan to the Alien and Sedition Acts, he was confident that the American people would eventually set things right, for he believed that deep down they were almost all virtuous republicans, and indeed Jeffersonian Republicans.

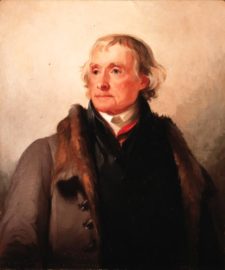

Thomas Jefferson, by Thomas Sully (1821)

And Jefferson believed that the people did set things right through what he immodestly called the “revolution of 1800,” by which he meant his own elevation to the presidency. His Federalist opponents were annihilated as a political force in the early years of the nineteenth century, and he was succeeded in the nation’s highest office first by his most trusted political partner, James Madison, and then by his longtime acolyte, James Monroe, for two terms each. It is unsurprising, therefore, that Jefferson retained a sense of hopefulness far longer than did figures like Washington, Hamilton, and Adams.

Yet in Jefferson’s final years he too came to despair for America’s future. His late-life loss of heart was brought on by a number of factors, but the central one was the sectional divide between North and South that came to light during the first great conflict over the expansion of slavery in America, the Missouri crisis of 1819–21.

In a famous letter of April 1820, Jefferson proclaimed that this conflict “like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union.” In the process of explaining the cause of his alarm, he all but prophesied the path to the Civil War: “a geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.”

Map of the Missouri Compromise 1820

Jefferson concluded the letter with an unforgettable expression of regret: “I am now to die in the belief that the useless sacrifice of themselves, by the generation of ’76. To acquire self-government and happiness to their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons, and that my only consolation is to be that I live not to weep over it.” One would be hard-pressed to compose a clearer, more forceful articulation of disillusionment than this, and it was far from an isolated moment of anguish on his part: Jefferson wrote seemingly countless letters on the Missouri crisis during this period, each more hysterical and apocalyptic than the last.

Jefferson was kept in the depths of despair in the years leading up to his death in 1826 by what he regarded as the illegitimate and dangerous centralization of political power within the federal government, even at the hands of his fellow Republicans. Indeed, he found this tendency so distressing that he began to wonder whether a breakup of the union might soon be not only inevitable, but desirable. In December 1825 he told one correspondent that “there can be no hesitation” when “the sole alternatives left are the dissolution of our union … or submission to a government without limitation of powers” – clearly implying that he found disunion preferable to the path that he believed the nation was then taking.

Jefferson’s grave site at Monticello (VA)

The following month, Jefferson wrote to another correspondent to bemoan “the evils which the present lowering aspect of our political horizon so ominously portends.” He had expected, he confessed, that “at some future day, which I hoped to be very distant, the free principles of our government might change … but I certainly did not expect that they would not over-live the generation which established them.”

Throughout Jefferson’s final years, in short, even his abiding faith in the American experiment grew emphatically riddled with doubts.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for part 1-4 of this blog series.

Dennis C. Rasmussen is Professor of Political Science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He is the author of four books, including Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders and The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought, which was shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award. Click here for part 1-4 of this blog series.