Christina’s life sentence is based on the argument that if she had taken Amber to the hospital in time, her daughter would not have died. Exactly when she should have called in this timely medical attention was never stated. However, to justify the conviction, Amber would have to have incurred the fatal injuries before Christina left for work on Tuesday April 14, 1992. After all: no one is denying that Christina took Amber to the hospital immediately upon returning home that day.

Imagining the waiting room of the medical center where Christina and David were told that Amber had passed away

The District Attorney told the media that he didn’t know who struck the fatal blows, because ‘they blamed each other’. One of the detectives who worked on the case said afterwards: ‘Did I know who struck the fatal blow? No. I looked at her as more guilty because she was her mother.’ And: ‘Personally, I think if the jury hadn’t known that she pled guilty to the homicide, they would have found David guilty.’

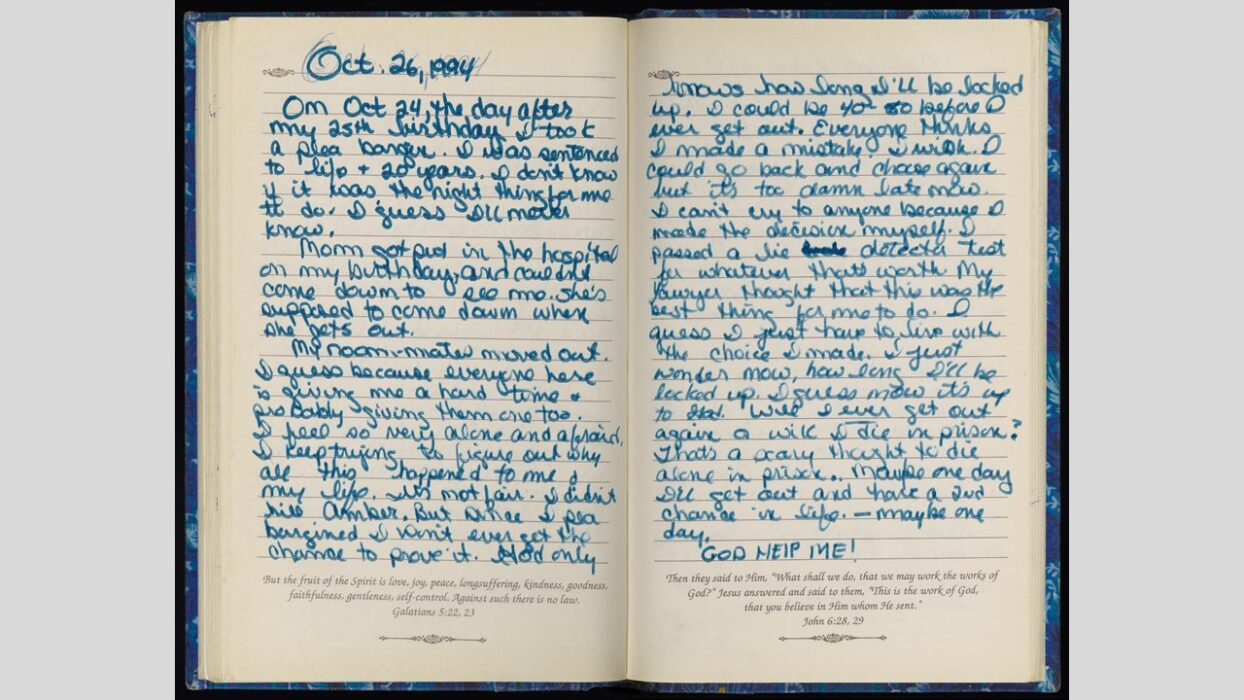

A devastating consequence of the kind of plea bargain Christina accepted is that it makes an appeal or reopening of the case – and therefore the possibility of the verdict being overturned – all but impossible. As one lawyer put it to Christina: ‘It doesn’t matter if you were on the moon when Amber died and NASA had pictures documenting it. You signed the plea and gave up your right to prove your innocence.’

Contrary to what we see in films and on TV, 95 percent of all criminal cases in America – just like Christina’s – don’t end up in front of a jury, but with a plea bargain: a deal, with a lesser punishment being offered in exchange for a guilty plea. Indigent defendants in particular, with a court-appointed, badly paid and usually sub-standard or overburdened pro bono lawyer, often give up their right to a trial – even if they are innocent.

Prosecutors are also under great pressure to make plea bargains. The United States incarcerates the highest percentage of its population of any country in the world, and if every case were to go to trial the system would collapse under the cost.

Christina was sentenced to life imprisonment with the possibility of parole. In theory, there is therefore a chance she could get out. The decision on this is taken by the five members of the Board of Pardons and Paroles. Owing to the overheated legal system, however, they are immensely overworked: each member has on average just a few minutes to make a decision on the fate of a prisoner.

On December 22, 2021, Christina’s parole was rejected for the ninth time. The argument was the same as on earlier occasions: ‘insufficient amount of time served to date given the nature and circumstances of your offense(s).’ On average, people convicted of murder now serve 29 years before parole. Christina, now 52, has been incarcerated for 30 years.

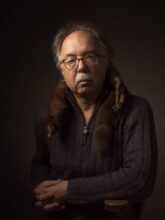

David was released on November 16, 2011. He is now married, and again living in Carrollton.

Christina and Amber in the park (1990) in Columbus, Ohio

This is the final part of ‘The Verdict: The Christina Boyer Case’. Click here for the complete series.

Artist-photographer Jan Banning has had more than 80 solo exhibitions in more than twenty countries, on four continents. His work is included in many public and corporate collections including those of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, the Forward Thinking Museum in New York City, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. His photographs have been published in dozens of newspapers and magazines worldwide, including The New Yorker, Time and Newsweek. His book ‘The Verdict’ is available in both Dutch and English. Click here for more information about the upcoming exhibtion in Rotterdam. There is also a podcast, called ‘Jan & Christina’.

public and corporate collections including those of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, the Forward Thinking Museum in New York City, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. His photographs have been published in dozens of newspapers and magazines worldwide, including The New Yorker, Time and Newsweek. His book ‘The Verdict’ is available in both Dutch and English. Click here for more information about the upcoming exhibtion in Rotterdam. There is also a podcast, called ‘Jan & Christina’.