Slavery stood at the center of the American experience prior to the Civil War. From the arrival of the first enslaved individuals in colonial Virginia in 1619, the issue of slavery gradually tore the nation apart. In particular, the nineteenth century witnessed increasing hostility between North and South over the “peculiar institution.” The volatile decade of the 1850s only furthered this with events such as Bleeding Kansas, the Caning of Charles Sumner, and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. These events, capped by the presidential election of Abraham Lincoln in the fall of 1860, paved the way for southern states to break away from the United States and form their own Confederate States of America under the leadership of former Senator and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. The secession winter of 1860-1861 witnessed largely a war of words before the onset of hostilities in Charleston, South Carolina in April 1861.

Rally in support of the Union, New York City, April 1861

The firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor transitioned the war to an armed conflict. Abraham Lincoln’s subsequent call for 75,000 soldiers to put down the insurrection pushed several more upper South states to secede—including the pivotal states of Virginia and North Carolina.

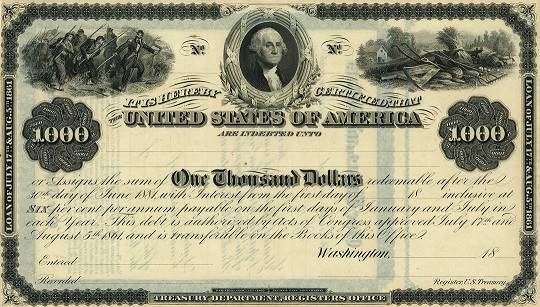

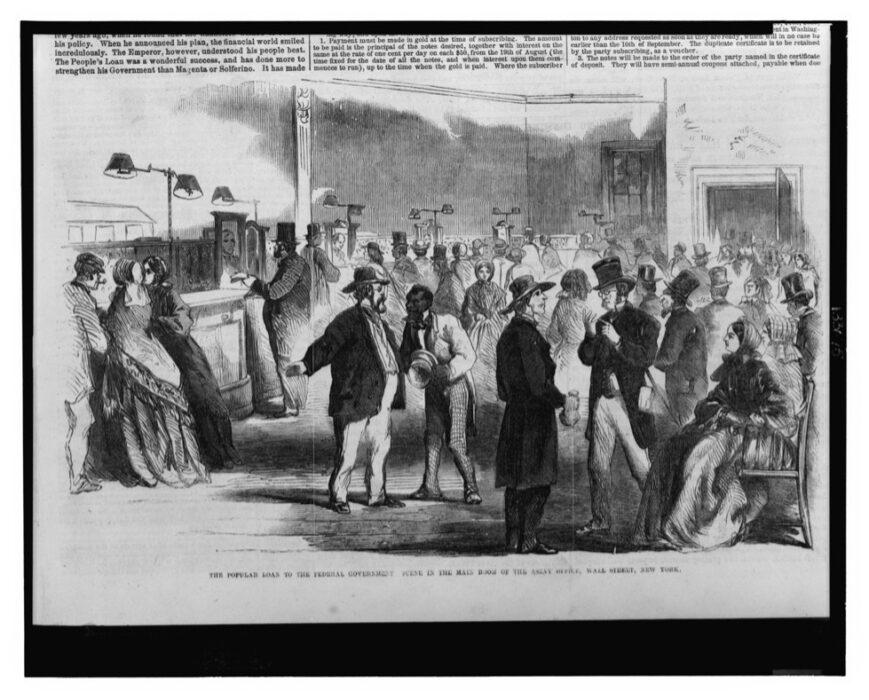

The war still remained one of a war for Union and not one to end slavery in the spring of 1861, but the possibility of a large-scale civil conflict from the most important western cotton provider made many wary across the Atlantic. While the United States government marshalled forces from across the North, they also had to determine how they would fund a standing army in the field (the cost of which would ultimately exceed $2 million a day.) Since the American Revolution, the United States had long relied on bond issues, effectively governmental IOU’s, to fund conflicts. In addition to international capital to help purchase these bonds, the government had increasingly come to rely on financial elites in the United States to take these bonds off their hands and handle the responsibility of selling these financial instruments to investors in the market. But the Civil War represented a new era. Wall Street financiers and their counterparts in cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and elsewhere simply could not (and in some instances would not) take on the debt of the American government writ large during the Civil War—a total sum in excess of $2 billion in 1860s money. Drastic changes in the United States even since the end of the Mexican War in 1848 meant monumental armies could take the field. Instead of a model more in line with the twentieth century of bond sales to the populace at large, the Lincoln administration first had to test the limitations of elite financial support in 1861.

Assay Office on Wall Street, the primary location in New York for investors to purchase U.S. government-issued bonds needed to finance the war

Central to all of this was Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase. Chase joined Lincoln’s cabinet as part of the “team of rivals” so that Lincoln could keep political threats close. Chase did not have a background in finance—rather he practiced law prior to the war and in particular defended fugitive enslaved individuals. Chase’s lack of financial acumen quickly was on full display. As he shuttled back and forth between Washington and New York City to secure funds for the federal government to conduct their war, it became abundantly clear that financiers on Wall Street would only extend so much faith and credit in the Union.

Salmon Chase, Secretary of the Treasury

Threats from Chase to flood the country with paper money—allegedly proclaiming that he would do so until breakfast cost $1,000—did nothing to move financial elites in his direction. By December 1861, the North had suspended specie payments, meaning you could not turn in notes for the equivalent amount of gold. Legislation out of Congress to create a new national currency and large bond issues did not resolve the fundamental problem, the government was running out of money. Chase needed a new approach and to do that he chose to rely on a little-known banker from Philadelphia. A man by the name of Jay Cooke. By entering into an arrangement with Cooke, Salmon Chase set the federal government on a new path. A path with implications not only for financing the Civil War, but beyond.

David K. Thomson is an Associate Professor of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, USA. Thomson’s focus is on the financial history of the American Civil War era.

David K. Thomson is an Associate Professor of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, USA. Thomson’s focus is on the financial history of the American Civil War era.

His first book on the topic, ‘Bonds of War’, published by the University of North Carolina Press in April 2022 traces the crucially important role of bond sales by the United States government during the war to fund the conflict. Thomson’s work has also been featured in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Bloomberg.

His first book on the topic, ‘Bonds of War’, published by the University of North Carolina Press in April 2022 traces the crucially important role of bond sales by the United States government during the war to fund the conflict. Thomson’s work has also been featured in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Bloomberg.